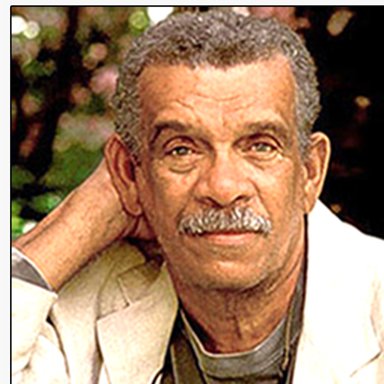

Derek Walcott used the history and the color of the Caribbean to tell his stories

Egbert Gaye

Derek Walcott was a true, true Caribbean man.

The pride that this literary giant harbored for the region from whence he came was reflected in much of his work in the 70-something years that he put pen to paper.

In staking out his place among the great writers of his time, Walcott repeatedly drew from the colonial history of the West Indies and the vibrancy of its language, culture and natural beauty to craft the 24 poetry collections, 25 plays and eight other books that have earned him international acclaim.

On October 8,1992, the year that marked the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s landing in the Caribbean, the committee announced that the St. Lucian-born poet and playwright had won the Nobel Prize For Literature.

In so doing, they commented: “West Indian culture has found its great poet.”

Having spent a good chunk of his life under the domination of European colonialism, Walcott understood more than most people the debilitating impact it had on the region, but used it to empower himself and his writings.

In his Wikipedia profile, he’s quoted as saying: “What we were deprived of was also our privilege. There was a great joy in making a world that so far, up to then, had been undefined… My generation of West Indian writers has felt such a powerful elation at having the privilege of writing about places and people for the first time and, simultaneously, having behind them the tradition of knowing how well it can be done—by a Defoe, a Dickens, a Richardson.”

And as such, all of his seminal work: poems and plays such as Omerus, Castaway, Dream on Monkey Mountain and Pantomime were constructed upon the imagery and oral culture of the West Indies.

One literary critic summed it up by saying:

“By using the West Indian theater as a showcase for the oral culture of the West Indies, Walcott hoped to create a more secure social identity for West Indians living under English rule.”

Another one saw Walcott’s voice as “an elegant West Indies murmur against history’s violent colonial narrative of bondage.”

Derek Walcott was born one of a twin in Castries, St. Lucia, in 1930. He grew up in a house where art and literature flourished, and was nourished by a regular diet of Shakespeare from his mother, who read to him constantly.

And when at 18, he decided to publish his first book of poetry, it was his mother, a seamstress, who scrapped and scrounged to find the $200 for him to send to Trinidad to have the book printed.

He hawked those copies on street corners and made back the money easily.

He earned a scholarship to study at the University College of The West Indies in Jamaica.

After finishing university in 1953, he settled in Trinidad where he worked as a journalist and established himself as a respectable playwright, writing several of his seminal plays and founding the Trinidad Theatre Workshop in 1959.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s he drew international acclaim with his growing list of poems, most of which touched on the Caribbean and its colonial and postcolonial shackles.

In 1990, he wrote Omeros probably his most influential poem, which earned him praise and renown from The New York Times Book Review and The Washington Post, and won him several literary awards.

The 64-chapter epic poem was divided into seven “books” and stood apart from other larger-than-life pieces of work because of the distinctive style and structure employed by Walcott.

The characters and parts of the storyline parallel the equally epic, The Iliad, by ancient Greek writer Homer.

The Times Review chose the book as one of its “Best Books of 1990” and in 1992 it earned Walcott the distinction of being the second Caribbean man to win the Nobel Prize For Literature.

(Saint John Perse of Guadeloupe in 1960 and VS Naipaul of Trinidad and Tobago won it in 2001.)

Also in a distinguished academic career, Walcott taught at the University of Boston, The University of Alberta and The University of Essex.

Among his many commendations, Walcott was named Officer of the Order of the British Empire and Knight of the Order of Saint Lucia.

On March 17, Derek Walcott died at his home at Cap Estate, Gros-Islet, Saint Lucia. He was 87 years old.

“The sigh of history rises over ruins, not over landscapes, and in the Antilles there are few ruins to sigh over, apart from the ruins of sugar estates and abandoned forts.”