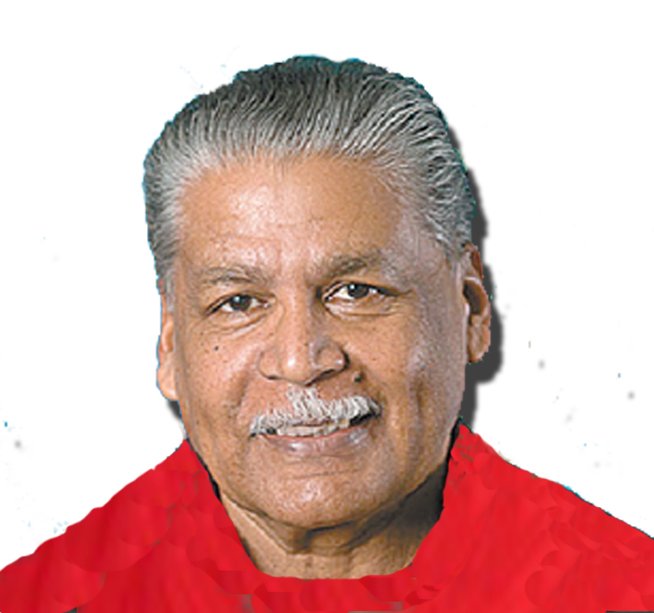

Raffique Shah, former rebel soldier now eminent journalist remembers the days of the revolution in T&T in 1970

Egbert Gaye

On April 21,  1970, Trinidad and Tobago found itself on the edge of a precipice.

1970, Trinidad and Tobago found itself on the edge of a precipice.

Events leading up to that fateful day when some 300 soldiers rose against their superiors and pledged their support to thousands of demonstrators had been gathering steam in the years following the nation’s independence in 1962.

And for a while the threat of mass bloodshed and widespread social unrest hung over the nation. The Black Power protests as they came to be known was triggered by a set of conditions in the newly independent nation that kept the majority of its Black population shut out of proper jobs, housing and meaningful access to opportunities.

The unfolding events would color the life of Raffique Shah, a young army officer, and install him permanently in the annals of history of Trinidad and Tobago.

By 1968, anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism movements in Latin America, Africa and Asia, together with the civil rights struggles in North America, not the least of which were the Black Writers Conference and the Sir George Williams Affair here in Montreal, helped fuel the disenchantment that became widespread across Trinidad and Tobago.

It all came to a head on that fateful day, 45 years ago, when the masses took a stand against the lingering vestiges of colonialism: thousands were on the streets marching, trade unions in the sugar and oil industries were threatening to cripple the economy with a general strike, and shouts of “Black Power” resonated in villages and cities across the island.

The government of the day, the People’s National Movement (PNM), was headed by Dr. Eric Williams who led the nation to independence, and was so iconic in his status that many on the island believed fervently that he was “the brightest (most intelligent) man in the whole world.”

In the face of the growing unrest, he shocked the nation and declared a state of emergency, arrested those perceived to be the leaders, about 50 of them, and called out the army.

Shah, then a 24-year-old lieutenant trained at the elite Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in England, was to take his platoon to the capital, Port of Spain, to maintain order.

Instead, he changed the country’s course of history when he turned his guns on his superiors in the army, and together with two fellow lieutenants, Rex Lassalle and Michael Bazie, both also Sandhurst trained, led the first mutiny in Trinidad and Tobago.

In the days following the takeover of Teteron, the headquarters of the Regiment in Chaguaramas on the northwestern tip of the island, Trinidad and Tobago was a tinderbox of uncertainty with looming prospects of widespread internal violence, conflict with regional powerhouse Venezuela and intervention by the United States.

Through it all, the names Shah and Lassalle lingered on the tip of every tongue in the country and beyond. For some, they were revolutionary heroes, to o thers, rebels.

thers, rebels.

In an extensive interview with the Montreal Community CONTACT, Shah, who just turned 69, remembers that pivotal period of his life and that of Trinidad and Tobago.

“Looking back, I wouldn’t say we were revolutionaries, instead I think we were romantics,” he says with a slight hint of laughter in his voice. “We certainly believed in everything that we were standing for and were prepared to die for them, but we were not prepared to kill for them. I think there is a certain level of romanticism believing that you can carry out a revolution without bloodshed.”

In what today stands as one of the “great speeches of Trinidad and Tobago,” Shah, during his eventual court-martial, reflected on the idealism that fueled his actions:

“Maybe like Ché (Guevara), and in his words, I’m more of an adventurer, only of a different sort—one of those who would risk their lives to prove what they believe. On the morning of April 21, 1970, I risked my life, and even today as I stand here before you (the court), I’m risking my life….”

As a backdrop to what happened that day, Shah tells of an early life colored by respect for humanity and hard work as dictated by his parents—father a sugar worker, mother a housewife.

He also acquired a passion to be of service to his Freeport community, a small multi-racial village in central Trinidad, and to his country.

He entered Sandhurst at a little over 18-years-old as one of the youngest officers in training, the only person of Indian descent in the batch from the Caribbean. He hardly even noticed the distinction because “in my life, race never mattered and never will.”

He returned to Trinidad, eager to help build a military that was progressive and open to the growth and potential of the soldiers that were being recruited to serve the newly independent nation.

But he and his fellow Sandhurst graduates realized that wasn’t about to happen any time soon in an institution where most of the leadership were affiliated to the ruling political party and were serving at the pleasure of Dr. Williams, a situation that put them on a collision course with the authorities in the army and the political leaders of the land.

Shah says their convictions leading up to 1970 were shaped by the writings and speeches of leaders involved in civil rights and human rights battles around the world. At Sandhurst, where the library brimmed with books and other sources of information, they read voraciously.

And although he and a small band stood ready to fight for the changes that they knew were necessary, nothing was written in stone.

“The truth is, although we had some informal conversations about taking over and bringing change to the army, there were no real plans on how we would go about it,” Shah says. “And we certainly weren’t ready for a revolution in the true sense of the word. The one thing that was a certainty is that we would not allow the government to use the army against the people of Trinidad and Tobago.”

So when the orders came that morning to deploy to Port of Spain to deal with the Black Power disturbances, Shah, Lassalle, Bazie and their co-conspirators knew that they had to act quickly, but they were making up as they went along.

Among the first order of business was to get his men to secure the bunker with the ammunition and then neutralize the high command.

Shah and Lassalle went to the office of the commanding officer, Colonel Stanley Johnson, to arrest him and inform him of the mutiny. He was not present so they turned their attention to Major Henry Christopher, the second-in-command.

Shah says when he attempted to place Christopher under arrest, the senior officer was so startled that he couldn’t understand what was happening and grabbed Shah’s rifle. And in the ensuing scuffle a round was fired off, which created a bit of turmoil around the barracks, during which he was arrested by a group of soldiers who also didn’t grasp what was taking place.

He was eventually freed, and within a few hours he and his men took control of the barracks.

“We took control of Teteron in less than an hour with about 20 rounds of ammunition,” he was to later write.

Eventually, Shah and Lassalle had about 300 soldiers—about half of the regiment at the time—under their command and had complete control of barracks, bunkers, telephone and all services.

Shah says immediately after the take-over, he mobilized a force to move into the capital, Port of Spain, to begin negotiations with the government.

However, what followed was an unexpected confrontation with the Coast Guard that tested the resolve of the rebel soldiers.

Before they were able to hit the road to Port of Spain, they began taking fire from the Coast Guard vessel Trinity, which had pulled into Teteron Bay.

Although the ship was well within range of the powerful weapons in the hands of the rebel soldiers, Shah said he made a conscious decision not to return fire.

“We could have blown them out of the water, but we had no fight with the coast guard.”

However, the altercation escalated as Shah and his men began their trek to the city. Another coast guard vessel in the area, the Staubles Bay, was being mobilized, and it’s only aircraft described as an old Cessna (9YA), hovered in the area.

As they attempted to move out of Teteron, Shah says the shells coming from the big guns of the Trinity that crashed into the hills around them had a very destabilizing impact on the men.

One soldier, Private Clyde Bailey, was injured in the bombardment and eventually died from his injuries. His injury severely tested the commitment of the rebels not to engage the coast guard.

“Many of them wanted to take out the two ships, which were there for the taking, but when Rex and I considered the massive loss of life that was going to result from that course of action, we decided that it’s best we return to Teteron.”

Over the next ten days, Shah and his men maintained their defensive positions at the barracks and he says they were prepared for any eventualities.

In the ensuing days, they maintained dialogue with the government, with Coast Guard Lt. Commander Mervyn Williams serving as the intermediary.

During the period between the take-over and the eventual surrender, there were one or two tense moments, including a near confrontation with Venezuela, which dispatched two frigates towards Teteron on the second day of the uprising.

That action caused Shah and his men to immediately prepare for battle, and according to reports other members of the defense force signaled their intentions to fight with the rebels if any foreign nation intervened.

Quick action by the government made the Venezuelans turn back and get out of Trinidad waters.

The path to a peace accord came after the rebels met with the then attorney general, Karl Hudson Phillips.

Among the demands Shah and his men put before the government was the firing of Colonel Johnson, the commanding officer of the regiment, and the reinstatement of a former CO, Colonel (Joffre) Serrette. They also called for the release of all political prisoners and amnesty for the rebel soldiers.

Col. Serrette was given command of the regiment on April 26, and he eventually betrayed the trust of the mutinous soldiers by orchestrating their arrest at what was supposed to be a reunification luncheon.

On May 1, 1970, Shah, Lassalle and Bazie were charged with treason and mutiny, both charges carrying the death penalty. In the ensuing days, some 85 other soldiers were also arrested and similarly charged.

Their court martial was conducted by 20 officers drawn from several Commonwealth countries under the supervision of Colonel Yakubu Danjuma of Nigeria, who himself was implicated in a coup in his country four years earlier. Another judge, Colonel Ignatius Acheompong of Ghana, returned home after the trial and orchestrated his own coup.

The trial lasted five months from October 1970 to March 1971 and ended with most of the officers and soldiers found guilty. Shah was given a 20-year sentence, Lassalle 15 years and Bazie, seven years.

However, the soldiers won their freedom at the Appeal Court and at the Privy Council in 1972, on a technicality based on a statement condoning the mutiny by their commanding officer, Col. Serrette. Condonation is a viable defense in a court martial.

When Shah and his brother-in-arm Lassalle walked out of the jail on Fredrick Street in the heart of Port of Spain, they were met by scores of jubilant supporters.

The relevance of what took place at Teteron Army Barracks between April 21 and May 1, 1970 is reflected in a list of significant changes in the military and on the political landscape of Trinidad and Tobago.

Some of these changes were identified by his attorney Desmond Allum at the tail end of the trial, including the removal of the minister in charge of the regiment, Minister of Home Affairs, Gerard Montano and its eventual transformation into the Ministry of National Security, who was fired and the reinstatement of Serrette as commander of the Regiment.

At 26-years-old in 1972, Raffique Shah was again a free man. And, in following his convictions, he had done more than most of his generation, but Trinidad hadn’t heard the last of him.

A few years later, he emerged as the leader of the Trinidad Islandwide Cane Farmers Union and became a founding member of the United Labor Front Party (ULF) in 1975, with then emerging Labor lawyer, Basdeo Panday and George Weeks and Joe Young, two firebrand labor leaders of the day.

In 1976, the ULF formed the Official Opposition of Trinidad & Tobago, with Shah serving as Leader of the Opposition between 1977-78.

A few years later, despondent that the ULF was being drawn into the politics of race that had blighted Trinidad for so many years, Shah walked away from electoral politics.

He still wasn’t done with Trinidad.

Right out of politics, he delved into journalism, serving as editor of the Trinidad Mirror, a weekly newspaper published by iconic newsman Patrick Chokolingo, and he continues to write a weekly column for the Trinidad Express.

Among all his exploits, one of the contributions that Shah is most proud of is his founding of the Mirror Marathon, which he established in 1986. Today, it stands as the Trinidad International Marathon, one of the best in the Caribbean that has attracted as many as 1200 runners at its peak.

Forty-five years after he imprinted himself on the conscience of the young nation, what for him was unconditional love has evolved into a more realistic view of Trinidad and Tobago.

He is disenchanted with the country’s slip into what has become wanton crime and criminality, and blames successive governments that contributed to what he described as “the dumbing down of the police force.”

He is also troubled by the growing disparity between the have and have-nots and the inability or unwillingness of politicians to do something about it.

A few years ago, Shah was quoted as saying that if everyone chose to leave Trinidad he would be the last guy under a coconut tree with his flag.

These days he says things are so bad, if he was 20 years younger, rather than finding other ways to bring about change, he might be thinking of packing his bags.

4 Comments

Marvel Mendez April 17, 2015 at 6:50 pm

6703 N.W. 7th Street

Marvel Mendez April 17, 2015 at 6:51 pm

Keep up the good work eg !

karin December 1, 2019 at 1:13 am

Joffre Serrette … Trinidad and tobago ..information please

Big Drum Nation March 26, 2023 at 9:15 am

[…] Tuesday, March 21, 2023 at 08:13:30 AM EDT, troppyh@aol.com <troppyh@aol.com> wrote: https://mtlcommunitycontact.com/revolution-at-the-doorsteps-of-trinidad-and-tobago/ On Tuesday, March 21, 2023 at 08:10:21 AM EDT, troppyh@aol.com <troppyh@aol.com> wrote: […]