A nation forged in pride now defined by determination

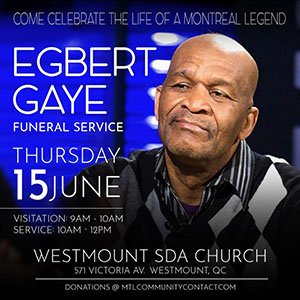

Egbert Gaye

Five years after the earthquake and four years after the election of Michel Martelly, the story of Haiti continues to be one of unfulfilled dreams.

When the 7.0 tremor quake struck on January 12, 2010, the devastation was widespread and life changing for the nation’s 10.5 million people.

Well over 300,000 were killed, another half a million or so injured and 1.5 million left homeless in a country that for much of its existence has been identified as one of the poorest in the world with an estimated three quarter of the population living on less than $US2 per day.

Among the dead were about 25% of Haiti’s administrators and political leaders.

Then to make things worse, in October 2010 a cholera outbreak, which was blamed on United Nations soldiers stationed on the island, started to further devastate the island, so far killing close to 10,000 and infecting close to 300,000.

The structural damage was just as intense, especially in and around the capital, Port Au Prince, where 300,000 houses, in addition to 80% of the country’s administrative buildings and schools were damaged or destroyed, creating almost 20 million cubic metres of rubble and debris.

Flattened and deflated, Haiti needed help from the outside world badly, but just as urgent, it needed Haitians to step up to lead in the rebuilding efforts.

One year later, the Haitian people voted for Michel Martelly, an entertainer turned politician who came with a promise to foster stability and growth. He had widespread political support not only among young Haitians but also in powerful international circles.

But the task of rebuilding infrastructure and regenerating the political system in a country where debilitating poverty and corruption have taken hold over decades is proving to be more than a challenge for Martelly.

Add to that an extended history of paternalism on the part of donor countries and donor agencies involved in the rebuilding process and you’ll understand why, after five years, the country does not have much to show for the US$10 to13 billion aid money the world donated following the earthquake.

Disaster relief experts estimate that just about $3 billion made it to Haiti and more than 90% of the money either went to United Nations agencies or to the 10,000 international non-governmental organizations that fall over each other to ply their trade on the island.

Five years after their world crumbled and in the midst of the chaos that the rebuilding effort has become, tens of thousands of displaced Haitians still wallow in makeshift shelters and live without some of the bare necessities, and for the most part Haiti remains a basket case. And according to one disaster relief expert, the strength of NGOs which have an unyielding hold on the money and the relief efforts and the weakness of the Haitian state makes for a troubling relationship that will keep the country in a constant state of need.

Also, the shaky political situation doesn’t help.

At a time when Haiti needs strong and confident internal leadership to counter the power of the NGOs and army of aid/humanitarian experts, President Martelly still cannot consolidate his hold on power.

Months of anti-government protests have already driven his appointed prime minister, Laurent Lamothe and his government ministers out of office.

The term of office for two-thirds of the 30-member Senate, the entire Lower Chamber and hundreds of local government elected officials came to an end in December and Martelly refuses to hold fresh elections, so he is now ruling by decree.

After opposition politicians spurned an attempt by the U.S. to broker a deal to extend the dysfunctional parliament, Martelly installed another prime minister, Evans Paul, a former mayor of the Capital Port au Prince, an 18-member cabinet and 16 secretaries of state to form another government until he decides to call elections.

But protesters and opposition politicians refuse to be placated and the protests continue.

As the country hobbles forward, the concern is that Martelly, who cannot seek office for another term, is buying time to put in place a hand picked successor.

Another concern is the frightening possibility of violence in a country that has seen more than its fair share of coups and military rule, including two in 1988, then in 1991 and 2004.

Through it all the Haitian people continue to show resilience and pride in a nation that was forged from the struggle for liberation by slaves who established the first independent nation in Latin America and the Caribbean.

And on their way to doing so, the army of slaves under the leadership of Toussaint L’Overture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines had to defeat three European superpowers: Britain, France and Spain, all of whom were set on keeping the Haitian people in bondage.

Such was the determination to witness the failure of the Haitian struggle for self-determination, the United States, which had also freed itself from colonial rule and all of Europe turned their backs on the fledgling republic.

It took them decades to recognize Haiti.

By 1914, they were all looking for reasons to invade the new republic. One year later, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt sent in the Marines and began a 20-year occupation of the island that ended in 1934.

After that, much of Haiti’s political history is mired in disorder and %%%% at the expense of the Haitian people.

In 1957, Francois Papa Doc Duvalier, a physician who earned his sobriquet from his relentless fight against diseases that were decimating Haiti’s poor came into power.

Papa Doc, a Black nationalist, carved out a 14-year rule that changed the political dynamic in Haiti by countering the influence of the mixed race class and empowering Black Haitians.

By the time of his death in 1971, he was able to put in place a Black middle class of significance in Haiti.

However, much of his tenure was marked by violence and repression and the emergence of the Ton Ton Macout, a rural militia force that did his biddings. He was replaced by his son, Jean ‘Baby Doc’ Claude who ruled until he was ousted in 1986.

After several attempts at military rule, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, another populist, emerged out of the belly of Haiti.

A Catholic priest who served much of his tenure in Port au Prince where he shared his interpretation of the Gospel based on the principles of liberation theology, was drawn into politics to answer the needs of the Haitian underclass.

In 1990, he became Haiti’s first democratically elected president, but was quickly ousted in a coup in 1991.

He came back into power in 1994 and served until 1996. Later that year he founded the Fanmi Lavaalas political party, which won the 2001 elections.

During his rule, Aristide demanded that France pay $21 billion to Haiti as restitution for the 90 million gold francs the country had to pay to its former colonizer.

He was ousted in a coup in 2004.

For the people, life has always been a process of picking up the pieces…and so it was until 4:52 pm on Tuesday, January 12, 2010, when their world crumbled again.