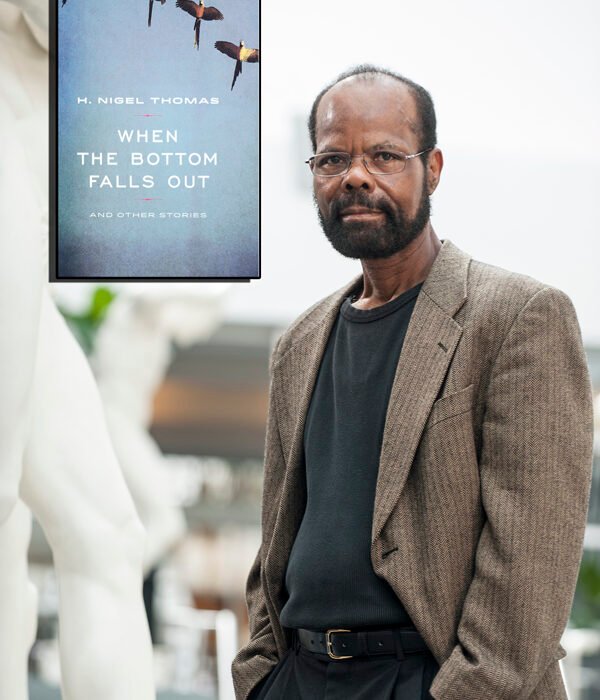

H. Nigel Thomas passion for the written word and his capacity as a writer has placed him among the luminaries of Canadian literature. He has also forged a successful career in academia as a professor of U.S. Literature at Université Laval between 1988 and 2006.

To date, Thomas, a graduate of Concordia University, McGill University and Université de Montréal, has nine published books: novels, short stories, literary criticism and poetry.

In 1994, he was shortlisted for the Hugh MacLennan Fiction Award; in 2000, he received the Montreal Association of Black Business Persons and Professionals Jackie Robinson Award for Professional of the Year; and in 2013, he received Université Laval’s award, Hommage aux créateurs for outstanding work in literary creation.

Now he is set on sharing his love of literature with the community by organizing a series of monthly literary sessions that will shine the spotlight on new and emerging writers in both the French and English sectors of the community.

The Kola Readings/Lectures Kola bilingual reading series of poetry, fiction and spoken word will be hosted by Thomas and Maguy Metellus. The first of these sessions will be on Monday, May 11, at 2741 Notre-Dame West (north east corner of Atwater, metro Lionel-Groulx) and will feature local writers Aldith Harrison, Kaie Kellough, Natacha Odonnat and Wesley Rigaud. The readings will be followed by an open mike period.

H. Nigel Thomas will also launch his latest book When the Bottom Falls Out and Other Stories, 2015, 2741 Notre-Dame West (north east corner of Atwater, metro Lionel-Groulx). 5:30 – 7:30 pm.

H. Nigel Thomas, When the Bottom Falls Out and other stories, Toronto, Ontario: TSAR Publication, 2014. (158 pages) Price $20.95.

Broken Lives in a Whirlpool of Evil

Novelist, short story writer and critic H. Nigel Thomas has written a fantastic collection of short stories that reveals universal truths about human nature and the human condition.

Like his other fictional works, When the Bottom Falls Out is set for the most part in Isabella, with some overlapping of location in time and place with Jamaica and Quebec. There is a plethora of themes that revolve around obeah, religious beliefs, sexual and economic exploitation of women by members of the planter class and Blacks in privileged positions. Colour and dominance, murder, ingratitude, sibling rivalry, deception, domestic violence and much more add to the list of themes.

The opening story, “Guilty and Innocent”, addresses the ubiquitous theme of wife beating and female abuse by spouses or male friends. Bertie beats his wife until she finally murders him. Although she is exonerated, when she dies a new Pastor from Kansas refuses to perform the burial ceremony. This story sets up a chain of events which are absurd and comical. The Pastor declares: “I ain’t committin’ her to the ground” (p.1). He refuses on the grounds that “Sister Roberta is an abomination unto the Lord. She done commit murder. And the Lord, He done tell me that she is a reprobate, to be cast in the pit on the last day.

Pastor Johnson violates God’s law by judging, and furthermore he does not bring sinners to repentance but casts them away as unbelievers, contrary to the will of the Lord. Sister McClean challenges the Pastor’s action and declares:

“Now when you tell me, you not committing her to the ground, I feel like we start the trial over again; and Pastor, I don’ think you have the right to ‘cause

God make the rain to fall on the just and the unjust.” (p.5)

Thomas uses all the Biblical stops to show the folly of the situation and the hypocrisy found in the church. This first story sets the mindscape for the jocularity and derision in the other stories that follow. It also shows how so-called believers appropriate the Bible in covering up dishonesty and untruths. The Pastor’s religious belief system is forcefully denounced by Sister McClean: “You don’t got the right to judge her Pastor. And I don’t care what the Bible says.”

“Caleb’s Tempest” deals with sex, the ridiculing of Blacks, crooked politicians and journalists. There is a preoccupation with colour, which permeates many of the stories. Privileges are granted to whites and Blacks of lighter skin colour over the black masses. The justice system, educational opportunities and economic advancement are all based on colour, rank and status. Whites get away with impunity in the courts while Blacks bear the brunt of the law for the slightest infractions. Thomas brings to the fore social inequities and the degraded conditions for Blacks in pre and post-independent Isabella. Under colonial rule corruption and wrongdoing are covered up; these same conditions prevail under Black rule. The poison of the colonial master infuses the veins of the new black rulers and the masses.

In colonial days, Pa Vaux tells Caleb:

In those days whenever you knew anything they were uncomfortable with and they couldn’t count on you to keep your mouth shut, they took you out. (p. 80).

Poverty makes the villagers turn a blind eye to the atrocities they suffer. Their livelihood depends on the planter class, hence sex, rapine, illegal sexual encounters with minors, abortion and other social wrongs are covered up, even to death.

“The Headmaster’s Visit” is about a depraved headmaster who abuses his position and breeds under-aged female students, causing unwanted pregnancy, abortion and even death. In his old age he summons a former male student and pours out his guilt before him.

Thomas uses landscape in this story much as Shakespeare does in King Lear to show the headmaster’s descent into his private madness. Twilight, the flowing river and the trees in the darkness tend to accentuate evil.

“I didn’t tell her to abort and kill herself.

I didn’t, I didn’t… She wasn’t quite fourteen. (p. 57)

This story presents a very poignant philosophy of life; broken lives in a whirlpool of guilt. The headmaster marries his wife at fourteen, simply to avoid her father’s wrath and his disgrace. She has four children and two abortions. He is recognized with an award, Member of the British Empire (MBE), but is never promoted in his field of education. His bitterness explodes as he speaks of the schoolgirls that he slept with and his depraved acts now haunt him as he drowns his guilty conscience in alcohol. His last desperate act is to ask Freddy to make love to him: “I always wanted to know what it feel like for a man to —- me – all my life – ain’t never had the courage.” (p. 61). The mighty has fallen and the lowly vindicated.

“Emory” extends the storyline of youth pregnancy, the suppression of truth, murder, vigilante justice, and the police and cover-ups. When rich whites commit murder they easily escape justice by being spirited out of the country. Emory as a policeman, sworn to uphold the law and protect the citizenry, is caught up with protecting fellow officers who breed teenage girls. Many times, he made the evidence of the acts disappear and counsels mothers to accept hush money and not disgrace their families. He fronts for the white police commissioner who protects drug dealers and collects large sums of money. Emory’s job is to make sure there are no arrests of the leading drug lords. He is also to prevent the competition from gaining a foothold in the business.

Emory lives with the guilt of his actions and on his deathbed wants to tell his daughter about his dealings, but before he could do so he commits suicide with an overdose of morphine.

It is not my intention to give highlights or a summary of each story. I use selected stories to indicate the range and depth of Thomas’s themes and to give a broad overview of how issues of morality, conscience and social issues are dealt with in the collection.

Thomas has a great knack of pulling the reader into these stories. As they become immersed in them in some sort of cathartic way, the dramatic cord is pulled back leaving the pitiful and painful to linger… The long view throughout the collection on what is right and what is wrong stands out. Thomas is also unflattering in his depiction of upper class society in Isabella and how the masses are duped into silence through fear and religious manipulation. He uses the Bible to poke fun at people’s foibles and proverbs therein to ridicule their folly. What is endearing to the reader is Thomas’s versatility in using island languages, be it Vincentian, Jamaican and French in the latter stories.

There is much to relish in these stories on an island where women use their bodies to survive, while producing more mouths to feed and deepening their suffering. By the end of the collection, the reader has a good knowledge of island culture, customs and practices from obeah to Methodist or Anglican doctrines to a Pentecostal flavour of religion. The upper classes belong to the Methodist or Anglican denominations. The poor seek their daily bread and their souls’ salvation in Pentecostal fire and brimstone dogma.

Through satire, Thomas is able to reveal the bottom of the characters’ greed, lust, ignorance and arrogance, depending on their station in life. The reader becomes a voyeur as s/he looks into the bedroom, fields/bushes and the private lives of the characters. The female characters face great hardships, isolation and abuse. Men for the most part are depicted as power-hungry, marauding sexual predators. The sea hauntingly lacerates the minds of the people with its harsh and constant lashing of the land. Everything seems dizzying as historical events collide with daily living to reflect the horrors and brutality of life. Inner and outer realities create darkness in the soul of man.

Read the stories and your lives will be changed from the bottom up.

Horace I. Goddard

1 Comment

h nigel thomas April 17, 2015 at 6:21 pm

Just to say thanks to Egbert and Dr. Goddard for the glowing review and the compliment, and to say that the launch of When the Bottom Falls out and Other Stories will take place on May 8, 2015, 5:30-7:30 pm at 2741 Notre Dame west (the UNIA premises), north-east corner of Notre-Dame and Atwater.