Is it any longer relevant in Montreal?

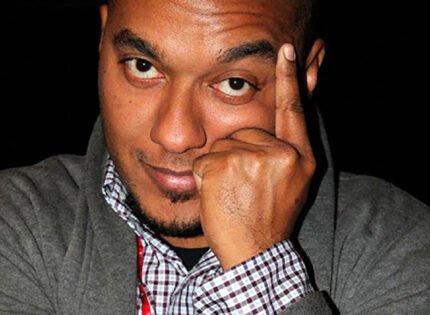

Clarence Bayne

Mr. Egbert Gaye, the editor-in-chief of Community Contact (Volume 28, Number 02 Jan, 26, 2018) in an interview featuring Michael Farkas, the President of the Black History Month Round Table (BHMRT) posed the question: “Is the celebration of Black History Month any longer relevant in Montreal?

Egbert, in the lead up to this question described the official opening event for Black History Month traditionally held at City Hall in a way that captures the feeling in the Black English speaking community. He said it is an event in which the Black English speaking community has lost interest, and from which they feel that they have been excluded.

By and large the key organizational leadership in the English speaking Black community have absented themselves from the event, and the same is true of the major Black French speaking organizational leaders.

Let me put it up front, I believe that the event in and of itself is important, but for it to be truly meaningful and not be mere smoke and mirrors, the City administration and Provincial government must show evidence that they are aggressively eliminating the systemic barriers to Blacks in their administrations and their distribution of resources.

In general, most Blacks I speak to do not believe that this is happening or will happen. Moreover, because of my working relationship with the BHMRT I have had to respond in private to many of the questions and observations made by Egbert in his interview with Michael.

So, in this article I am going to pretend that I am being interviewed and responding to Community Contact and several other community leaders from the English speaking community questioning me, as in fact they have, about the relevance of the celebration and the significance of the events at City Hall.

The first question. “Clarence as a leader in this Black community and a Professor I do not have to tell you that Black history is about life, survival, and living. We do that every day. So why you and your friends get together with the City to celebrate Black History for only one month in the year? Do you feel that makes sense?”

The first thing I do when I attempt to answer this question is to get out of this leadership role that is so gratuitously being assigned to me. Because it usually is a trap, part of what I call the Moses syndrome. So I make the point that I need to breathe fresh air, drink clean water, and to be safe from the cold and other inhospitable things like “bad mouthers” reproduce myself and feel good. But I can’t do that to the maximum possible without making sure that some others also survive.

So I do what I have to do (act responsibly) so that my true friends and my family all have a better chance. So let’s drop the preamble, “as a leader, etc…” Moreover, being a professor is how I make a living salary. That’s it.

Having said that, I agree with those that say “Black history month is every day.” But I think that when we compare Black activities and visibility in the early sixties with today, we are living our history and reproducing our cultures as a people incredibly more than we were then.

Unfortunately we are doing it under great stress and negation by the mainstream white culture and the levellers/assassins in our own community. Part of the problem is that we have no one telling our stories and singing the praises of our achievements between the events at city hall.

So we are more likely to hear the voice of the personality assassinator than the creative voice of achievement and hope.

But the reality is that the activities that our children take for granted today and question did not exist in 1960: there were only 5,000 Blacks living mostly in Little Burgundy; there were only three Montreal-born Blacks at McGill University and Sir George Williams University; Mr. Stanley Clyke with a Master’s degree could only find work as a porter with CNR; there was no Black Theatre Workshop; no Vues d’Afrique; no Nuits d’Afrique, no Black Film Festival; no Carifiesta; no Reggae Festivals; no Jamaica Day, no Trini Day; no Oliver Jones; no Charlie Biddle; no Oscar Peterson; no Blue Ribbon or DouDou Boicel Jazz Festival; no calypsonians; no Eddie Toussaint, no Zab Maboungou, no West Can, no Taste of the Caribbean; no African and Caribbean restaurants; no Caribbean Associations, no Black doctors or nurses, no university-trained managers and professionals.

Blacks were trapped in low paying jobs as porters with CNR and CPR, suffered discrimination at most restaurants, night clubs and bars, and were not permitted to rent in most neighbourhoods of the city.

We began to push back the barriers to our progress from the mid-sixties during the “quiet revolution.” The Sir George Williams computer crisis, the Black Writers Congress, the creation of the National Black Coalition of Canada represent high points in the struggle to change the inhospitable landscape that we met in the late fifties and early sixties.

In 1991, a group of activists went down to City Hall and told the mayor that we are fed-up with being excluded from the cultural, social and economic proprietorship of this City and Province and that we wanted our culture and contributions recognized.

We wanted greater strategic control in the social, cultural and economic life of the City. The City Administration of the day, under Mayor Jean Doré, agreed.

The City not only agreed but became engaged in getting the province to put in place a Table de Concertation to address the broader issues of racial discrimination and the economic isolation of the Black community in Montreal and Quebec. To accommodate this the Black Community Forum was created in July 1992 to mobilize the Black English speaking Black communities.

Concretely, one of the things the City and the Black Community leadership agreed to was to adopt the Black American model for Black History Month and officially declare February Black History Month to be celebrated by all Montrealers.

This declaration did not give ownership to the City Administration. Nobody owns Black History Month. It is a time for celebration of our presence and contributions and get some recognition of the contributions of bauxite, sugar, cotton, banana, rum, citrus and slave labour to the development of the British Empire and Canada. God knows, in the English speaking Caribbean we ate a lot of salt fish tail and processed salted herrings not suitable for European markets to keep cost cheap and profits high for the Canadians and its booming Maritime economies of the time.

In effect, “Black History Month” in North America and the Caribbean evolves out of the English speaking Black experiences of the triangular mercantile trade, and slavery and capitalism. It is a celebration of the victory of the Western Black over the hell hole of plantation slavery. It is about the embracing of hope and the march to the “mountain top.”

It would be crazy for us as Blacks to say that the City and Province should stop this symbolic and official recognition of Blacks, that only Blacks should celebrate Black History month. The latter would defeat the purpose of the event here in Canada. What we need to do is to get the mainstream to learn more about us and incorporate our contributions in a valid and more integrated history of Montreal and Quebec.

That has to be a struggle that we must engage in above all else. This is not about hobnobbing with ministers, mayors and Prime Ministers. We cannot just allow City officials, policy makers and administrators to think that all they have to do is invite us to City Hall once a year and that we will be satisfied with a superficial type of fraternization.

Unfortunately, this is what many activists in the English speaking Black community believe has happened since 1992. And clearly they do not like it. That is the message that we are getting.