Sabrina Jafralie: “it’s as if it’s our first year of teaching…”

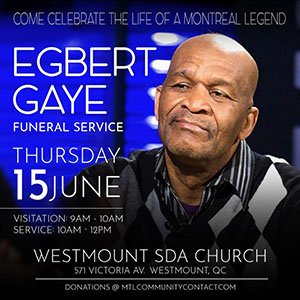

Egbert Gaye

Sabrina Jafralie carries her passion for teaching on her sleeves.

In the 20 years that she has been a Quebec Ethics and Religious Culture teacher at Westmount High School, hers has been a respected voice on a range of issues faced by English-speaking students and educators in the province.

Many of these issues, such as Bill 21, the religious symbol law and the absence of adequate teaching material relating to current social justice debates, continue to be relevant but with the spectre of COVID-19, Jafralie says it’s a whole new world in the classroom.

“As far as teaching is concerned, I think 2019 was the last year of the world as we once knew it to be,” she told the CONTACT in a telephone interview, recently. “It’s not the same game.”

“For the average teacher, it’s as if it’s our first year of teaching,” she says. “We are being forced to learn new ways of doing everything.”

Jafralie, who holds a Ph.D. with a specialization in ‘Teacher and Religious Education’ from McGill University estimates that education at the public high school level in Quebec will be set back at least two or three years because of the virus.

At the time of the interview, more than 400 schools across the province reportedly had at least one positive case of COVID-19; a Montreal area high school had to be shut down for two weeks because of an outbreak and several areas across the province were in the designated Orange-alert category.

Realities, which she says lead to anxiety and frustration for many teachers who “crave stability” in order to plan and carry out their duties.

“There’s no stability because everything can be shut down at anytime.

In the meantime, Jafralie says, as teachers and students try to respect the endless flow of government protocols and directives, fear and anxiety run rampant: “These days everyone is afraid of everything.”

And it’s impacting the teacher-student relationship.

“Many teachers instinctively get close to kids to make that they are getting the subject matter correct, but now, we can’t touch; we can’t even lean over their shoulders.”

“One of our challenges going forward is rebuilding the way we connect with the kids.”

She says the principal and staff at her school, which has a student population of about 900, have done an excellent job at establishing protocols for social distancing and bubbles.

“We have the arrows, red lines and designated entrances and exits all clearly identified but in the end, kids will be kids so there will always be issues.”

She pointed to how difficult it is for some students to keep their masks on at all times the confusion that confronts many of the younger students or those with special need having to restrain their natural inclination to hug teachers.

As well as the challenges of the new hybrid system in the advance grades that allows groups of students to attend school three days per week while others study at home.

“Basically, we’re asking 15 and 16 year olds to organize themselves at home… that’s never an easy task.”

As such she says the dynamics that are at play because of COVID-19 highlight a new level of interdependence among parents, school and students.

Adding that it has always been a delicate relationship between teachers and parents but as it is today, parents have to step up more.

Jafralie, who prides herself on her community service and her advocacy on behalf of students, says it’s good for students to be back in school because “I really do think that school is the safest place for them.”

However, she heaps most of the blame for the current imbroglio on the shoulders of the Quebec government.

“Number one: there should have been more consultations with school boards and educators before sending students back to school.

The opening date should have been delayed because administrators and teachers needed more time to prepare.”

She says during this time of crisis government priorities on education “are a little off.”

Here they’re fighting to establish service centres to replace school boards when they have been throwing money into schools to reduce class sizes in order to make it safer for students as well as teachers.

In the face of the myriad of challenges teachers face in this “new normal” in their profession, Jafralie is confident that at the end of the day, their Number One priority will be to their students.

“Teachers will always do what’s best for students.”