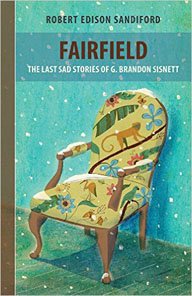

Book Review

Robert Edison Sandiford’s,

. Reviewed by H. Nigel Thomas

DC Books, Short fiction , 144 pp, $18.95

Fairfield: The Last Sad Stories of G. Brandon Sisnett is Robert Edison Sandiford’s third collection of short fiction. There are thirteen titles that the author identifies as stories; in fact, there are fourteen inasmuch as the “Prologue” is also fiction.

Some of the stories are linked, and characters from Sandiford’s novel And Sometimes They Fly and his first short story collection: Winter, Spring, Summer Fall, also show up here. Present too is his earlier foray into magic realism. According to the prologue, the stories have been authored by G. Brandson Sisnett, and the name Fairfield recurs “as city, state of mind, person, or idea of characters and places.” (2) In essence, Sandiford, if one trusts the prologue (one shouldn’t), assumes a double persona, that of author and acquisitions editor of the stories. The truth, however, is that the prologue suggests ways of reading and linking the stories.

In “The Big O” and “Funk,” two stories that feature Orville Sobers, and “Michel,” we again meet the character-narrator Edson Cumberbatch whom we first encountered in Winter, Spring, Summer , Fall. Although the interaction among siblings, which is the focus in Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall, continues in “Michel,” it is, however, the enigmatic nature of marital relationships that is Sandiford’s primary focus.

The Fairfield stories depict gradations of marital relationships. There are those that last: Bradford and Maddie’s (“They Build Houses Here Now”), the Linton’s (“Madame Tussaud’s Garden”), and the Cumberbatch’s, Edson’s parents (“Funk: ) Edson tells the reader that in earliest years his parents quarreled over every little thing, and then suddenly they stopped. “It occurred to me[that] my parents may simply have been together long enough at the time to voice their regret at some of their choices.” (143). This statement is pivotal inasmuch as it implies that being able to resign oneself to or accommodate intra-marital conflict might be part of the reason some marriages survive while others fail.

There are those relationships characterized by sexual infidelity: Orville and Yvette’s, in “Funk,” and Justin and Helene’s, in “Northern Lights.” In both cases the women are unfaithful, and they seem genuinely puzzled by their need to cheat. There are hints here and there that neither Orville nor Justin understood the women they married. Indeed Orville’s subconscious seemed to tell him that his marriage was wrong; he became almost catatonic when he was called upon to state the marriage vows. But can anyone truly understand another person? Do we even understand ourselves? The reader is more trusting of Orville’s story largely because the narrator knows Orville. The men are the devastated ones. These are themes that only a middle-aged writer can confidently explore. Both stories are further enriched by their blues tone and settings.

The story “Michel” merits special attention. It’s an excellent depiction of bullying, if not of downright sociopathy. Sandiford shows not only the bully in action but the desperate measures the victim engages in to palliate the effects of bullying. It is also Sandiford’s return to the theme of sibling rivalry; this time, however, with a perspective enlarged by the knowledge and wisdom gained from experience. Early in the story the reader wonders whether Bert, Edson’s older brother, isn’t a repressed version of Roy, the bully-sociopath, but later learns that he has become a respectable professional.

Sandiford’s penchant for speculative fiction, as shown in And Sometimes They Fly and The Tree of Youth, is present in three of the Fairfield stories. “The Jumbie Tribe” features the ghost of a Lebanese merchant standing on a street corner in Bridgetown, Barbados recalling his life and uncovering an ugly reality that only he, because of his jumbie omniscience, can know. “Screensaver,” like Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “An Old Man with Enormous Wings,” employs an unlikely situation to proffer oblique social commentary. This story too makes the reader think of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis.” Its tone is gentler than Kafka’s and is consonant with one of the major preoccupations of the collection: the invaluable benefits of family real and adopted. The third story “Massiah” projects a Barbados of the future. It offers brilliant insights into the machinations of power and the lies of which history is rife.

Two of the stories are about artists. “The Hours In-Between,” where the detective Julius McDuff from And Sometimes They Fly reappears, focuses on finding a motive for the suicide of Jeffrey James, literary novelist, turned writer of “police procedurals.” McDuff, who is also Jeffrey’s friend and informal student, is at Jeffrey’s home, the suicide scene. Along with the police he is trying to come up with a motive for the suicide. The story soon turns to reflections on another suicide: Mittelholzer’s self-immolation. No motive is found, not even McDuff, who believes he can communicate with the dead, finds one. But Sandiford provides clues. There’s the comfortable house which Jeffrey sacrificed his vocation to acquire and maintain. Some truths hold across millennia: gain at the expense of one’s soul is of little worth.

The other story, “Dance a Little,” contrasts with the first. Gary Spellman, upon hearing about the death of Michael Jackson and his father’s admiration for the military genius of Lt Lance, decides to leave everything behind and live for his art. He is fifty. The story comes with a note of caution, however. Lt Lance, for all his military genius—his ability to get his lost men safely out of the desert—died a drunk in an almshouse. Michael Jackson’s death was almost as inglorious. But Jackson and Lance had “guts” and exemplified it, and Spellman thinks the time has come for him to prove to himself that he does too.

There are two stories where the reader’s attention focuses on language. “Thick ‘n’ Thin” is written completely in Barbadian, a first for Sandiford. The other story, “Mobbed by the BBC” draws our attention to what’s left out when we translate or even paraphrase another’s language.

This collection offer some lovable characters dealing with grim aspects of existence, beautiful prose, and many moments for reflection on life’s enigmas and complexity.

Please note that Robert Sandiford will appear at the Kola Readings on April 11 (2741 Notre-Dame West at 7 pm), and at The Blue Metropolis Literary Festival on April 14 (Hotel 10, 10 Sherbrooke St. W, Salle Jardin at 7:30 pm).