There was a time when the Quebec education system was even less accommodating to Black students than it appears to be today.

A time when many students coming to Montreal from the Caribbean were being arbitrarily funneled to special-needs schools where, grouped with learners with real disabilities they struggled to make it to college and to university.

“For the handful of Black educators at the time, it was troubling to see,” says Garvin Jeffers. “ Because we knew what the children were experiencing was not an inability to learn but culture shock. So, we had to do something.”

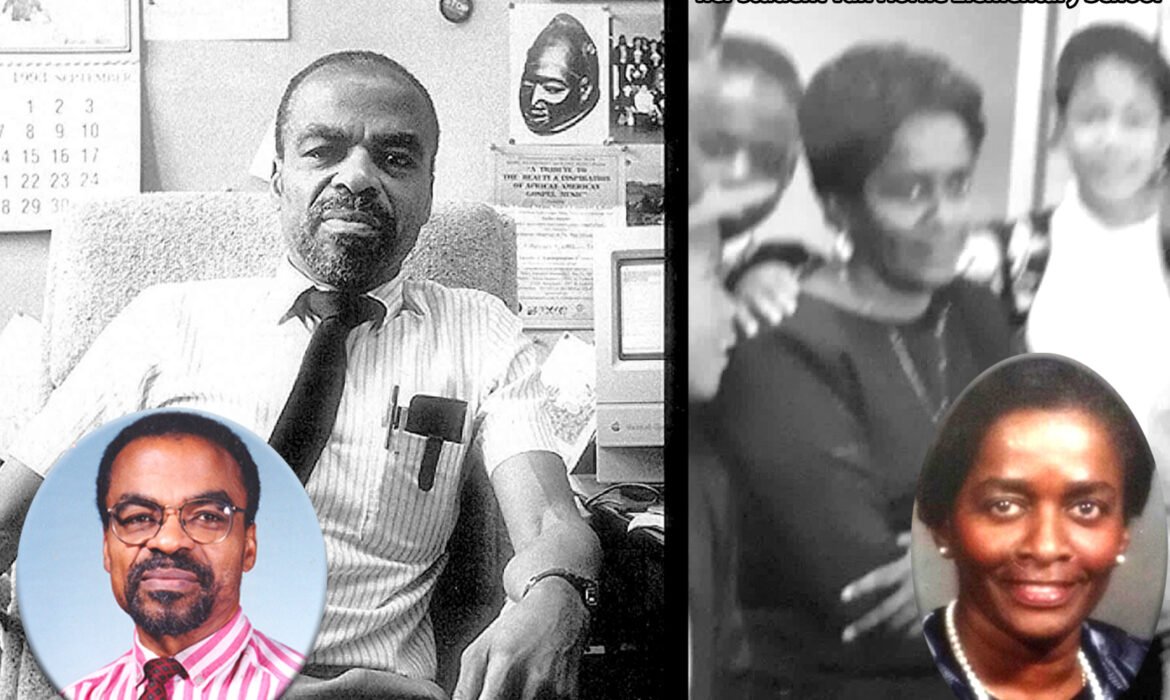

At an individual level, Mr. Jeffers who graduated from McDonald’s Teachers’ College in 1961 after earning his undergraduate degree from McGill University in 1960, started offering Saturday morning classes at his west island home to students.

He was joined initially by Mrs. Sybil Ince-Mercer and eventually other Black educators in this initiative that continued from his home to a centre in Roxboro then to Riverdale High for more than two decades.

Just as important, Jeffers joined with a handful of other Black educators and formed The Quebec Board of Black Educators (QBBE) as an advocacy force dedicated to “vigorously promote the welfare and well-being of Black students.”

This group, which included academic luminaries such as Oswald Downes, Leo Bertley, Ashton Lewis, Mrs. Sybil Ince-Mercer, Clarence Baynes, Selby Blackman, Marion McLean, Junior Wilson and a few others, was faced with an uphill task trying to wrestle concessions on behalf of Black students from the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal (PSBGM) under whose auspices many of them fell.

According to Jeffers, the level of disconnect between Black students and the system at the time was frightening.

For the most part he said, many students brought into a new and foreign learning environment were unable to cope with the shock. The school board responded by having them tested and placed into school for special needs students.

The need for advocacy on their behalf was overwhelming. Enter the QBBE in 1968 and with Downes a Trinidad-born educator serving as its first president the organization went on the offensive.

As one of the stalwarts on the frontlines, Mrs. Sybil Ince-Mercer remembered the urgency of the situation and how important it was for Black educators to take a stand on behalf of Black students.

“There was just a handful of us and we were concerned about the impact that the schoolboard’s actions was having on the Black students,” she said in a recent telephone conversation with The CONTACT. “That’s why we decided to do something about it.”

Mrs. Ince-Mercer who moved to Montreal in 1967, started teaching at Van Horn Elementary a year later. She remained with the PSBGM and later the English Montreal School Board for 36 years, retiring in 2004.

She says her work outside the formal classroom on behalf of Black students carried just as much significance.

She was the first to join Mr. Jeffers with Saturday-morning tutorial program and played a big role in the establishment of the QBBE and its supplementary education initiatives.

When Dr. Leo Bertley created the DaCosta Hall Summer Program to assist students in their transition from high school to college and university, Mrs. Ince-Mercer was front and center, helping him implement it.

And was also central in the implementation of the BANA Summer Program, created by Mr. Jeffers to assist elementary school students.

Looking back, Mr. Jeffers says that the QBBE, fueled by the energy and intellectual fortitude of its founders and early membership was vital in helping to adjust the landscape for both Black students and Black educators.

One of their first demands to the school board was for the establishment of a Black liaison officer, which led to the appointment of another stalwart, Ms. Gwen Lord to the position.

Ms. Lord went on to become the first Black administrator in the PSBGM, when she was appointed principal at Northmount High then serving for many years as a director at the board.

Jeffers, a well-respected mathematics teacher also rose through the ranks. After tenures at Rosemount High, Riverdale High and High School of Montreal, he was named a department head at Westmount High then served as vice principal for three years and principal for two years before his retirement in 1996.

Today it’s easy to gauge the impact, that the QBBE has had on Quebec’s education system for Black students as well as for Black educators, many of whom have elevated to the highest levels.

Following Mr. Downes, Ashton Lewis served as president and then Curtis George took over the reign at the QBBE for many years. But joining them in their lasting advocacy was an army of committed educators and community workers.

In a moment of reflection, Jeffers remarked about the lack of respect and recognition heaped on many of the foundation members recently as the QBBE marked its 50th anniversary celebration.

“I did not receive a call nor did many others who sacrificed a lot in building the QBBE,” he remarked, with a hint of disappointment.

But he jolted quickly back to his easy-going and positive disposition.

“It was never about us… it was about the students and the teachers who were coming after us.”