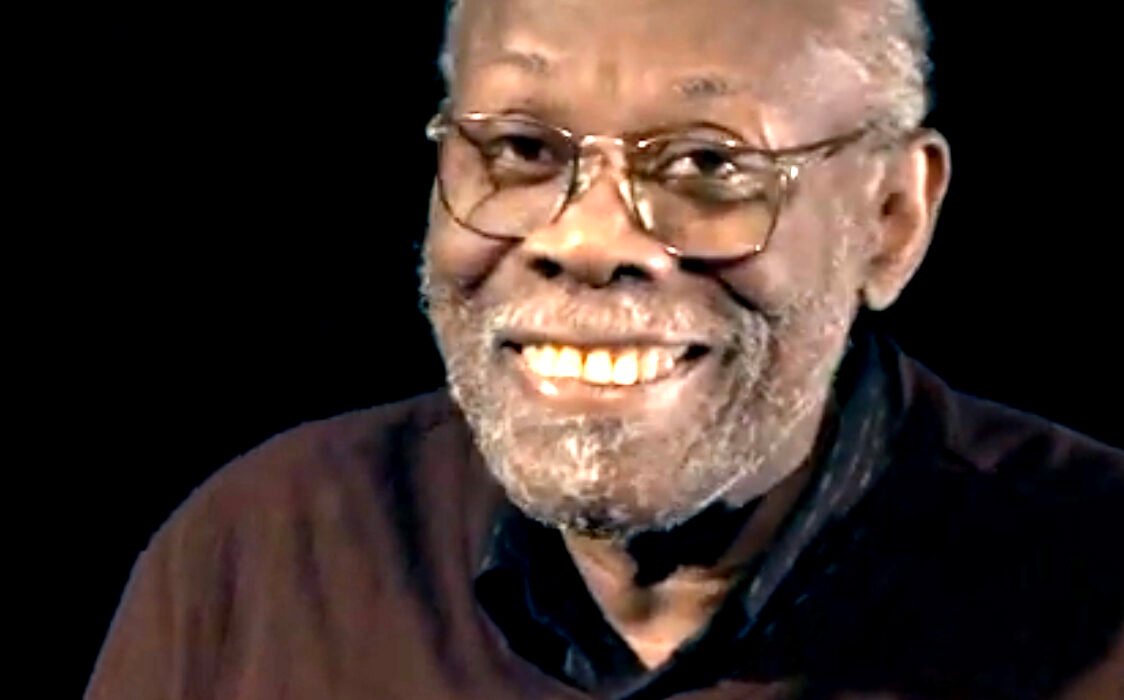

I first knew Clarence Bayne (CB) only by sight, seeing him on the 102 or 105 bus just over 40 years ago. To me, he was Judy and Patrice’s father, the man from D e Black community. But to say that he “worked” in the Black community is an understatement. Clarence worked for the community. His primary focus was the Black community, but by extension, Montreal, which was his home. As time passed, “community” for him meant the world around him. He was fully aware that if you did your part in the world, it would have a ripple effect on the larger world.

Clarence was a builder, an artist and a verbal force. By the early 2000s, he could say thank you in under four minutes. Before then, he could keep you on the phone engaged in an “ole talk” or a meeting for hours. He was a writer, an educator, and a visionary. Stubborn at times and set in his ways, he was also my mentor and friend. We strategized with many people, ate many meals together drank everywhere together. Many times, we were 3 with Fred Anderson but in the latter years it continued to be us two.

I’ve been extremely privileged to benefit from the efforts of so many individuals like Clarence, who came to this country and, upon realizing they weren’t adequately represented or had their needs met, decided to do something about it. They gathered in kitchens, halls, basements or anywhere they could to brainstorm and collaboratively foster a vision. Together, they charted a plan to build the community, brick by brick, creating organizations and initiatives that not only built Quebec and Canada that provided for the Black community.

Dr. Clarence S. Bayne, also known as Clary, was one of these storied individuals. Born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, Clarence left the twin-island republic in 1955 to study economics at the University of British Columbia. He earned a BA in Political Science and Economics, as well as a master’s in economics. In 1960, he arrived in Montreal, married Frances Ward—whom many of us called Aunty Fran—and began working as an economist with Canadian National Railway. He later enrolled at McGill University for his PhD and started teaching in the Economics Department at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia) in 1961. By 1966, he was a full-time faculty member in the Faculty of Commerce and Administration. He earned his PhD in 1977, and when he retired, he was one of Concordia University’s longest-serving Professor Emeritus at the John Molson School of Business, as well as the Director of the Institute for Community Entrepreneurship and Development.

I met CB when I was 15, through Grace Basso, another community soldier. She was the mother of my high school buddy, Noreen, and was running for commissioner of the PSBGM (now EMSB). I worked on Mrs. Basso’s campaign, and though she didn’t win, I wasn’t off the hook. Grace had Carl Whittaker make me a youth representative on the board of the Black Community Council of Quebec. At my first board meeting, I was overwhelmed and anxious. The imposter syndrome was real. I recall CB, Carl, Grace, Raymond Ferguson, Michael Gittens, Roy Gittens, Louise Durant, and Audley Legore being there. Passion (and volume) escalated quickly, with CB being the loudest. I thought he and Carl might come to blows, but at the end of the meeting, Clarence said, “… I’ll buy the first drink… you’re buying the rest!” They all left as friends. I was shocked! I hadn’t ever experienced anything things like it before. Grace explained that they’d been fighting for years, but it wasn’t personal. That was the first of many lessons Clarence taught me: Fight the positions, not the people.

Long before this, Clarence had fought many battles and was known for his passion—sometimes cussing—while working with community leaders like Dr. Dorothy Wills to start the National Black Coalition of Canada. CB, who had little patience for students focused only on fixing the Caribbean, called them hypocrites, telling them they wanted to control the Caribbean by “remote control.” Shortly after, a tragic incident in Nova Scotia—where a Black child was refused burial in a white cemetery—caught the attention of Clarence and Dorothy. They rallied 49 Black organizations from across Canada and enlisted community activist, Howard McCurdy to go to Nova Scotia to pressure Premier G.I. Smith to allow the burial. Their success and collective activism led to the birth of the National Black Coalition of Canada, with Clarence serving as the first President and Dorothy as National Secretary.

A large part of Clarence’s soul was dedicated to the arts and culture. During Expo 67 in Montreal, Clarence played a key role in the Trinidad and Tobago pavilion, managing the concession stand alongside Earl and Grace Basso and Shirley Whittaker alongside others. This was more than just a temporary effort, as musicians continued playing in the venue long after Expo ended.

In the late 1960s, CB co-founded the Black Studies Centre and was involved with the Trinidad and Tobago Drama Committee. His leadership extended into the 1970s, where he was instrumental in fostering a new kind of activism that drew on the emerging Black intellectual movements around the world. His approach was always grassroots, strategic, and political focused on what could be done in the present to improve the future. Conferences, poetry evenings, art exhibitions and gatherings were part of his efforts.

One of CB’s greatest legacies was the co-founding of the Black Theatre Workshop (BTW). What started as an idea among friends in an apartment in the McGill Ghetto grew into a significant cultural institution. As the BTW’s first Artistic Director, Clarence’s vision laid the foundation for countless actors, writers, and directors who passed through its doors. Clarence directed some of the plays, wore red leotards in a production and kept everyone focused on what this platform for Black self-expression could be. Today, BTW continues to produce work that resonates across Quebec and beyond.

Clarence wasn’t one to back down from a fight, whether it was arguing with university officials during the Sir George Williams University affair or calling Prime Minister Mulroney’s office in outrage when funding for Black organizations was delayed. His fearlessness and dedication often led to breakthroughs, such as the creation of the Black History Month Table at Montreal’s City Hall, a first for the city. Significant funding for Black community initiatives and significant partnerships with legions of organizations both inside and outside the Black community.

Over the years, Clarence’s contributions spanned academia, arts, and community development. His influence extended to initiatives like the Quebec Board of Black Educators, the Black Community Resource Centre which is curt one of the most dynamic organizations in our midst. He supported artists, entrepreneurs, and activists, and helped build a foundation for generations to come.

At his core, Clarence was a private man, deeply passionate about his family and friends. Though not without flaws, his impact on the community was undeniable. His legacy lives on through his children and the organizations he helped build, the people he mentored, and the countless lives he touched. With Fran by his side in most of his endeavours they contributed significantly to society.

Clary taught me many things, including the importance of working with the people who are ready to move forward with you, that the work should continue even after one leaf, and most importantly, that we must take care of each other. Always make your voices heard.

Rest in perfect peace, CB. And thank you. Too many people do not know the depth of your contribution. Most of it for no pay.