Wrongful dismissal after 18 years as a correctional officer at RDP Detention Center

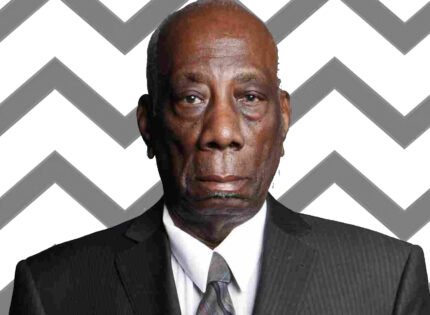

Egbert Gaye

“When a correctional service agent earns a promotion to become a unit chief, it’s a dream come true,” says Olivier Louis.

He knows. Having spent 18 years in the service and witnessed how much his co-workers aspired to get to that other level.

“It’s the aspiration of all agents, because there is no other path to go forward in the job.”

However, to get to that much-aspired position, correction workers in prisons across Quebec are required to write a provincial exam, titled: concours de chef d’unite en etablissement detention before which they are given a posting.

After almost two decades at Rivière-des-Prairies Detention Centre, Louis says there has never been a unit chief who is Black.

“For one reason or the other no Black person at this institution has ever been able to pass this exam,” he muses.

So in 2012, after being encouraged by “some of my colleagues, I decided that I’d write the exams. I knew without a doubt that I was capable of passing it,” says Louis, who holds a degree in Psychology from Concordia University and diplomas in Philosophy, Law and Industrial Relations from University of Montreal.

True to his beliefs, he was successful and became the first Black to be placed in the aptitude bank at Rivière-des-Prairies in line for a position as unit chief, which would have placed him in command of a zone in the prison with about 80 prisoners and 10 correctional officers.

Within a few months he was fired.

And his dismissal meant no compensation and none of the benefits that should have been accrued after more than 18 years on the job.

The 58-year-old was just two years shy of his retirement, due in April 2017.

“The only way to put this dismissal in perspective is to say that after so many years seeing us as subordinates, it was not normal for my superiors to see a Black person pass this exam and to be in line for a promotion. It was a shock to them,” Louis told the CONTACT at a recent sit-down. “And the way they dealt with it was to get rid of me.”

Before writing and passing the exam, Louis who was born Haiti and came to Canada when he was 17, says he was seen as a model worker at RDP prison, which sits on the northwestern edge of Montreal, not far from Laval.

There, his functions were multiple and included welcoming new prisoners, assisting with psychosocial and suicide evaluations and academic and recreational activities. He also represented the institution at conferences and seminars. He also worked for 14 years as an educator with the ministry of Social Services.

When in June 2012 he received news from the Quebec government that he was one of three correctional agents from RDP who was successful in the exam, he prepared himself to serve the remainder of his tenure with the pride and dignity that his expected position carried.

So he waited expectantly for the call to come.

It wasn’t long before the two other agents received their postings as unit chiefs. He grew worried when he saw one or two who didn’t even write the exams being named to positions as interims. He knew that after a year, if he wasn’t placed his name is automatically removed from the aptitude bank and he would have to rewrite the tests.

Louis says he grew worried.

After a few months he sent a letter to his superior and cringed when the terse reply came stating that he will be on vacation and gave the date of his return. When his superior returned and nothing happened, Louis fired off a complaint to the provincial ministry of Public Security.

Only then was he called to a meeting with his boss, who informed him that he wasn’t promoted because four other managers “didn’t like him and didn’t want to work with him.”

Louis says he was struck by the silliness of what was being presented to him, but he also started to realize the futility of his situation: his dream was not going to come true.

He began to sink into a deep depression. His doctor suggested some time off.

So he retreated into his proverbial cave to lick his wounds. But he says management at the prison wasn’t done with him.

A few weeks into his medical leave and still reeling from the indignity of being denied the career opportunity of his lifetime simply because of the whims and what he determined to be the racist attitude of a few individuals, he received a call from management asking him to see a psychiatrist.

“I realized that I was caught in an ugly game because I spent less than ten minutes in her presence and she determined that I was capable of going back to work,” he says. “There I was still having nightmares… still dreaming that they had given me my promotion… still suffering.”

He says his doctor didn’t think he was ready to go back to the job, so he continued on his medical leave.

Less than a week before he was due to return to work on January 27, 2013, Louis says he received a call from his union informing him that he was terminated.

“The reason they gave was that I failed to attend a medical arbitration. I said I knew nothing about it. They said a letter was delivered to my doorsteps by a bailiff. I never saw it.”

The case ended up in front of a Quebec judge. The bailiff says he was instructed by the prison to leave the letter on Louis’ doorstep, which he did and the onus was on the former correctional agent to find it.

His dismissal stood.

Today, his only hope of salvaging his dignity and maybe compensation for the many years of service he rendered to Quebec stands with the Quebec Human Rights Commission, who has launched an investigation into his case.

And although he admits to being wounded by unimaginable injustice that has been imposed on him, Louis refuses to admit defeat and remains unbowed.

“If I had to, I’ll do it all over again because I always had a clean file on the job. They had nothing on me, but everything changed when I passed the exam and was entitled to a promotion. Then I became the worst person in the world.”

He said his situation is emblematic of the environment for minorities employed in the correctional services.

He describes it as a toxic and highly stressed environment in which racism festers, and more than once he had to challenge his colleagues for racist rants or actions. But for the most part he had to let many things slide in order to maintain his place as part of the team.

“I knew that by passing this exam, it was going to create a problem, but I never expected it to end this way. However, I have children born here and there are a lot of other minorities who will be making their way into the correction services, so whatever sacrifices I make, it is for them.”