Thirty years after the murder of Anthony Griffin by police officer Allan Gossett the relationship

between police and community is still strained

Contact Staff

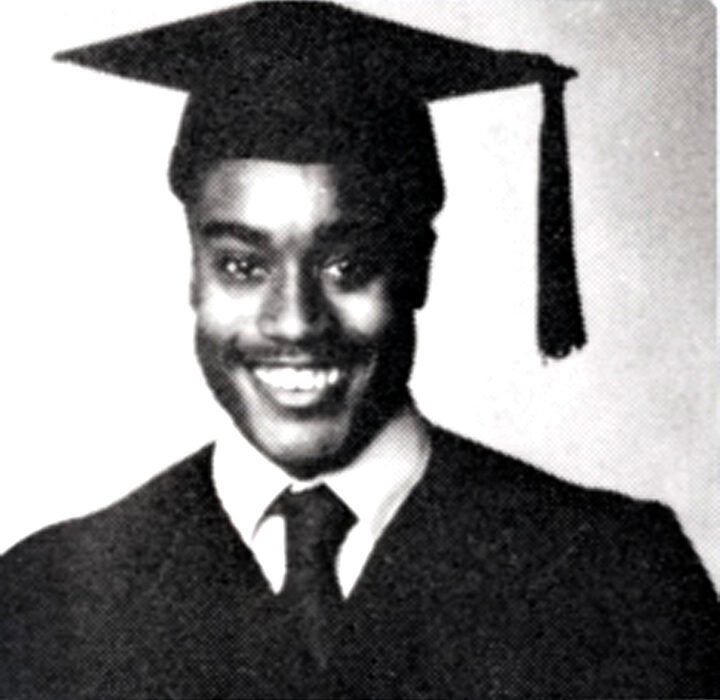

Anthony Griffin was just 19 years old, that morning on November 11, 1987, when he was shot and killed in cold blood, as they say, by constable Allan Gossett of the Montreal Police Department.

As the story went at the time, Griffin got into an altercation with a taxi driver over a $27 fare that resulted in a call to the police.

When they arrived Gossett decided to arrest Griffin because they found an outstanding warrant for a ‘Tony Griffin’ and proceeded to take him to Station 15, then situated on Mariette Street in NDG.

Once at the station, the police reported that Griffin, who was not handcuffed, got out of the car and ran.

Gossett pulled out his revolver and ordered him to stop. He did and was reportedly facing the police officer when he was shot between the eyes.

Griffin’s murder sparked an outburst of anger in the community and among people of good conscience across Montreal, many of whom took to the streets to protest police brutality and called on governments to hold the force accountable for their action.

In the eyes of many, Gossett wasn’t held accountable. In February 1988, about three months after he gunned down Griffin, the police officer was found not guilty on manslaughter charges and walked.

To add insult to injury, he also walked away unscathed from a $1.5 million civil lawsuit with the judge awarding the Griffin family a mere $25,000.

Even after he was fired by then police chief Roland Bourget, Gossett went to court and was reinstated into the force.

An appeal of Gossett’s manslaughter clearance went all the way to the Supreme Court but he again was able to beat the second manslaughter trial in 1989 before he eventually resigned from the force.

For Dan Philip and other community advocates, Griffin’s murder and the political and legal slap in the face heaped on his family was a trigger to challenge the Quebec government to examine the state of the relationship between police and the Black community.

Philip, head of the Black Coalition of Quebec, remembers the heft that accompanied the community as they engaged the government on the matter of police brutality and wanton abuse of power.

“It was a lot easier for us at the time, because the community itself was more engaged,” he told The CONTACT in a recent telephone interview. “We had more active organizations and it was way easier to mobilize people to come out on the street to protest.”

Outside of the community other groups were just as energized, especially on college and university campuses across the city, and their collective frustration overflowed in the street in a massive manifestation of protest with thousands of Montrealers calling on the government to act and for Gossett to be charged with murder instead of manslaughter.

In the face of unrelenting advocacy, the government responded and appointed lawyer Jacques Bellemare to head a commission of inquiry into police relations with the Black community and other marginalized groups in society.

He came up with a number of recommendations, about 70 in total, much of which were shelved, as were recommendations from other commissions of inquiry following other police killings such as the Malouf report that came after the police shooting of Marcellus Francois in 1991.

Over the decades, a handful of policy and structural changes were instituted in an attempt to mitigate police behavior as they relate to the Black community and other marginalized groups.

One is the establishment of the police ethics commission (la Déontogie Policiére) to “enforce the Code of ethics of Québec police officers.” Twenty-five years after it was put into place, it would be difficult to find any Black person who has found justification from that department.

Just as impotent and useless is the Bureau des enquêtes indépendantes, supposedly an independent civilian review unit put in place to investigate incidents where death or serious injury of civilians results from police actions.

For decades advocates have been calling for it seeing the futility of police investigating police, as has been the case here in Quebec from Day One.

The Parti Quebecois government instituted the unit in 2013. It should have been made up of 16 investigators; half of them retired police officers, and eight civilians.

However, a Montreal Gazette report in April last year showed at that time, although several high paying positions were filled by former law enforcement people, the unit was yet to become functional. Not much has been heard from them since.

In the meantime, many young Blacks and other minorities have been killed, brutalized and abuse by the Montreal police since Griffin; to date, no officer has had to pay for his action.

So the distrust continues.

Michael Farkas, head of Youth in Motion, an organization based in Little Burgundy that offers service to young Blacks and other minority youth, is on the frontline in the on-going conflict.

“Nothing much has changed since Anthony Griffin,” he says emphatically, “because our youth are still at risk when confronted by the police.”

“We still hear of young men and even young women being roughed up by police on a regular basis. And there are so many instances of police overacting and treating Blacks as suspects when they see them driving a nice car. So there is little trust on both sides.”

Farkas points to the much-vaunted Eclipse anti-gang squad, which was put together by the SPVM in 2008, as a source of continuous abuse of young Blacks on city streets.

He says this group of officers is in constant conflict with promoters and those attending hip hop events in the downtown, adding that they are known to go into bars and other establishment to provoke Black youth.

Philip says he too has had many complaints from those who have faced the wrath of Eclipse officers.

“These officers are also running loose in neighborhoods where there are many poor and disadvantaged people and they can abuse people with impunity,” he says. “Look at the outpouring of support that Guy Ouellet had when he was arrested, unjustly as many are saying. Where are those same people when Blacks are arrested for no good reasons.”

“When it comes to reversing systemic racism you cannot have a group that can do whatever they like and the government refuses to act because they too fear alienating certain sectors of society.”

Farkas says Blacks are still too much on the receiving end of injustice and abuse.

“We still cannot feel as if we are first class citizens in Quebec, Black youth even less so.”

Sadly, Philip says, many in our community have advanced to the point where we don’t think it’s necessary to have to fight for our rights anymore, and as such we’re at the hands of the police.