Former standout athlete and educator to receive Montreal Cares Lifetime Award

By Maria Anastasia

Weekes

Sometime this past March, Denburk Reid and his Montreal Community Cares Foundation team unanimously voted for Ivan Livingstone to receive the Montreal Community Cares Lifetime Achievement Award.

And he will be honored on May 11, at an award ceremony at Loyola High School, 2477 West Broadway. The annual event is an elegant fundraiser themed ‘It Takes A Village’, which celebrates role models and community do-gooders.

And it will be an opportunity for Montreal to learn more about Ivan Livingstone, a man born in 1929 in Verdun, a city then unraveled by the Great Depression, and who grew up in a the world that had little to offer children since the Canadian economy focused on war.

But Livingstone didn’t need much because the little he received from the world around him he used to build a spectacular life in academia, as a professional athlete and then in community advocacy, all of which positioned him to today, at the age of 89, to receive an MCC Lifetime Achievement Award.

“What’s this all about?” Livingstone asks, looking puzzled about getting recognized for nothing, because all his trophies and scholarships have a story of competition or kindness behind them. He feels comfortable about those. This one, for a lifetime of excellence from childhood to retirement, makes him think…

We got together last August at a monthly lunch held for seniors, who attended the NCC and Union United Church as kids.

I sat beside him because he wasn’t in the thick of the crowded dining room that was brimming with chatter. I introduced myself. He said hello, but his eyes were cold.

It never dawned on me that this stranger might have told his story on countless occasions because it coincides with the shaping of race relations in Montreal.

In high school, the adolescent learned whom teachers expected to excel and whom they

undermined. For Livingston, most of them reacted negatively, including calling him names, when he soared to victory either academically or as an athlete that forced him to orient himself towards the praise of the few to nurture his competitive spirit.

Of course it paid off because he stands as the first ever student-athlete at Verdun High School to earn the Grads Memorial Trophy in 1948.

Even then he remembers a female teacher stopping him in the hall and explained that the trophy belonged to a white kid, but the number of votes that earned him the distinction of being valedictorian confirmed that the trophy representing his overall academic-athletic performance was in the right hands.

Livingstone knew that his focus in high school had been about academics but he had used sports as currency to open doors then closed to lower-income families.

“If I had lived in different circumstances, I would have looked at sports as a fancy,” he continues, “in my particular case, it was [my way in].”

His first scholarship offer was from Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, but his father who was providing for a 14-member family couldn’t afford the ticket to get him to the school.

Seeing the high school senior’s potential fading, a teacher contacted McGill University admissions and secured a scholarship for him.

So, in September 1948 Livingstone entered the Agricultural Science program at MacDonald campus where he earned Varsity letters in track and field and football.

But it wasn’t all fun and games because his presence at football practice and the games brought to the fore an abundance of hostility and pettiness.

For his part, he was there to win at all cost. When the team won, his coach and mates rewarded him with silence. When they lost, he was blamed.

On the flipside, the freshman met international students from the Caribbean and Africa from whom he learned who Black people with fewer obstacles and more expectations, really were.

He seemed to develop real appreciation for his Jamaican-Guyanese background. One of his friends, a graduate student, told him that he needed to be at a school that valued his talent.

That led to a search that ended with Dubuque University in Iowa, which offered Livingstone a full scholarship in track and field.

The young Montréal milked this opportunity and earned his undergraduate degree with his mind set on going into Medicine.

He also earned the distinction of being the most decorated athlete in a given year, a record that remains unbeaten today.

His dream: return home, work and save for medical school—never materialized.

Livingstone came home, yes.

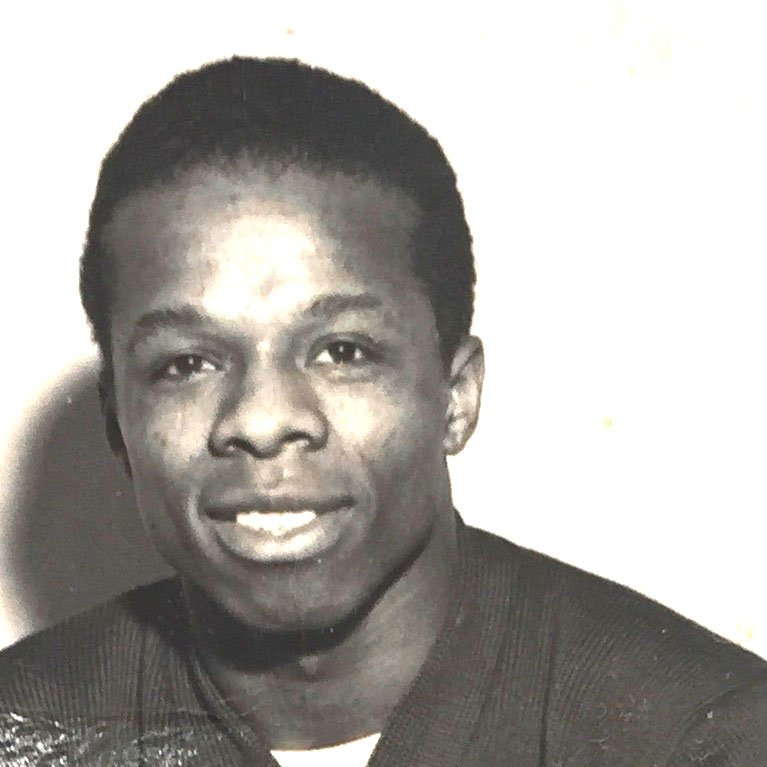

He played football with the Verdun Bulldogs, excelling to the point where he brought the scouts in the Canadian Football League to his door.

His seven-year career, from 1954 to 1960 and three teams, the Calgary Stampeders, BC Lions and Montreal Alouettes, exposed progress in terms of race relations with teammates since his McGill days, but still problematic.

His time in the CFL is immortalized on Topps football card 45.

Upon retirement from pro football, he embarked on the life that would eventually mold him into being a role model for our community and beyond.

He entered the work force in the 1950s as private institutions as well as different levels of governments were seeking workers with new skills, especially in computer science or French skills.

Also, as the politics of multiculturalism began to take root Livingstone, a fully bilingual and highly-trained chemist was actively sought out by the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal (PSBGM) who offered him a contract to teach chemistry and French, making him the first Black teacher at the school board.

And his presence at Verdun High School as a teacher meant Black students had a role model that allowed them to see options beyond welfare, delivery jobs, train porters, music and sports.

It also meant that he and some former teachers, who never believed he’d passed his station just by excelling in school, had become colleagues. Same, when he became a commissioner at the South Shore English Regional School Board in the early 1980s.

Between that time, Livingstone says he was “repotted,” a transplant that had less to do with having gotten married and becoming a father three times over and more with his time in Africa and settling into his Africanness.

He moved to the Democratic Republic of Congo where he taught Chemistry at the RIAD Institute under a project sponsored by the Canadian International Development Agency which allowed him to research issues closer to his heart.

However, when he became director of the program, his appointment sat uncomfortably with white colleagues. Eventually, he moved on to Benin and Gabon, documenting daily life and religious customs for his post graduate thesis.

Today, his home in Montreal’s Golden Square Mile, many districts away from his birthplace, is decorated with artifacts from the continent, memorabilia of events from the 1980s, an image of Miles Davis, a jazz collection and tons of authors, including Chinua Achebe.

Through our conversations, I’ve learned that many of his workplace experiences are mine. More importantly they clarified many unanswered questions and provided a perspective from which to understand the so-called tools to improve race relations.

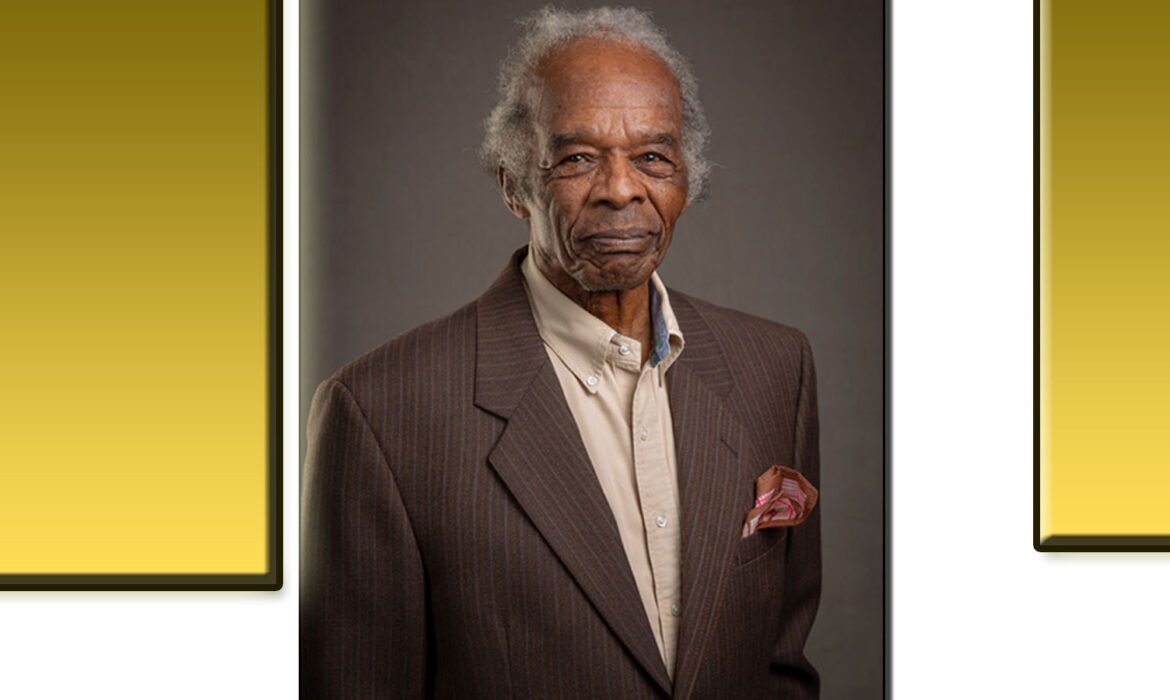

Ivan Livingstone, April 2019

Image by MCC Awards team

For tickets go to:

https://montrealcommunitycares.com/tickets