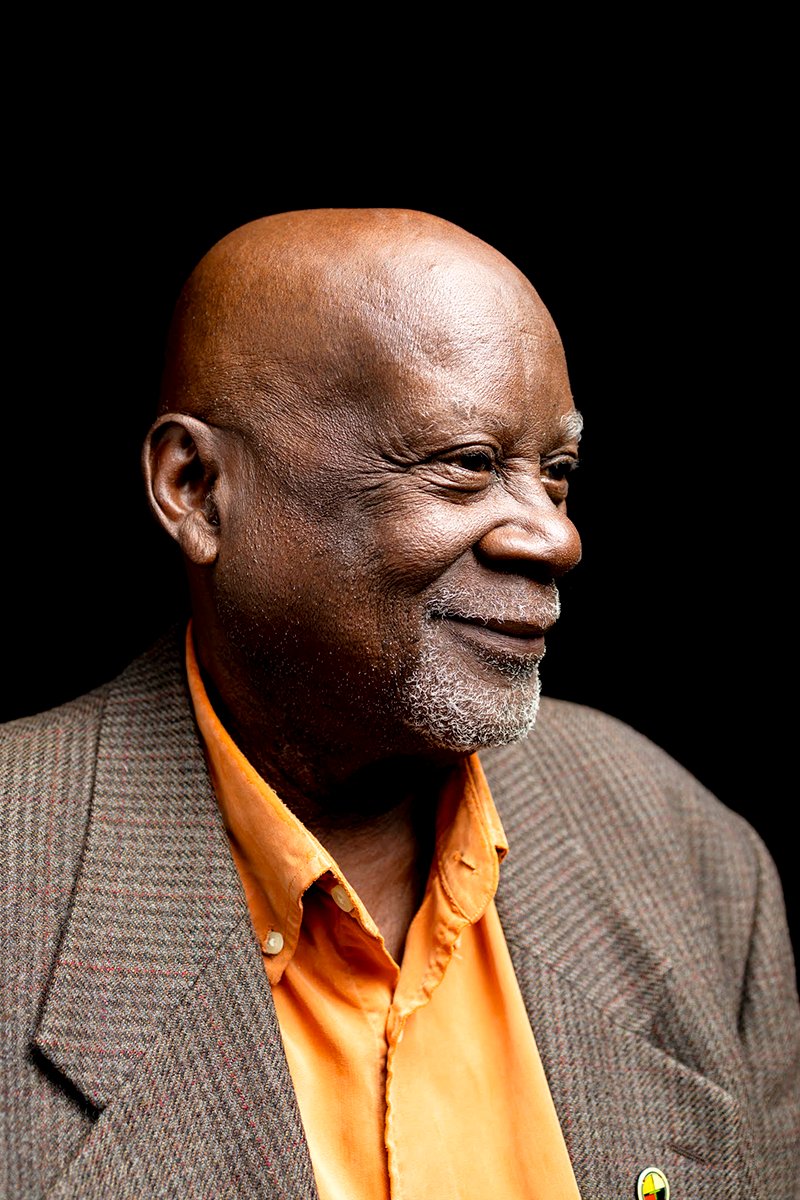

In a conversation with the CONTACT, that moved from Montreal’s Black media legacy to the backroads of Mississippi, author and longtime community advocate Fred Anderson didn’t just detail what happened in his life he explained why he could no longer let it remain unwritten.

In a conversation with the CONTACT, that moved from Montreal’s Black media legacy to the backroads of Mississippi, author and longtime community advocate Fred Anderson didn’t just detail what happened in his life he explained why he could no longer let it remain unwritten.

Anderson’s memoir, Eyes Have Seen: From Mississippi to Montreal, is not only a coming-of-age story about growing up Black in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, in the 1950s and 60s. It’s also a record of exile of fleeing to Canada as a Vietnam War resister in 1966, living under an assumed name for 11 years, and building a new life in Montreal while carrying the weight of the South on his back.

But when asked what made him finally sit down and document it all, Anderson was clear: it wasn’t just about him.

“One of the driving forces of my determination to write my memoir and my story,” he said, “was to showcase the courage of so many ordinary local Black people who were the true foot soldiers and underpinning of the Civil Rights Movement.”

The interview began with a reminder that community journalism has always been a form of resistance in Montreal. Anderson recalled his time as assistant director at the Negro Community Centre, where a Black newspaper was being produced work that helped shape a generation of Black media makers.

“At that time, Egbert Gaye stepped up as a volunteer,” Anderson said, referring to Community Contact’s late founder and managing editor. “And also, Ron Charles, who went on to become quite an entity at CBC.”

It was a full-circle moment: as he remembered how the pages were built, while the next generation now holding the recorder recognized the importance of that lineage.

“You can’t become what you don’t see,” I told him. “I stand on his shoulders. He stood on yours.”

Then, with the ease of someone who has told these stories in his head a thousand times, Anderson took us back to where it began.

Anderson was born in 1947 in a Hattiesburg that was “totally segregated,” he said, even as the city had its own long tradition of resistance against white supremacy.

Some memories, however, weren’t about politics they were about survival.

He was eight years old when Emmett Till was murdered, and the brutality of it shook Black families across the South.

“I can vividly remember any time my mother would take me downtown into the white sector to shop,” he said. “She squeezed and held my hand so much tighter.”

The murder site, he noted, was only a few hours from his hometown. And when Black train porters arrived with magazines showing the horrifying photographs, the terror became public, undeniable something carried into homes, churches, conversations, and a mother’s grip.

At 15, Anderson left home and became an organizer with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), then associated with figures like John Lewis, Stokely Carmichael, and Bob Moses.

But his first assignment came with a warning: doing this work in Hattiesburg could put his family in danger.

“They said, ‘You can’t do this in Hattiesburg it would expose your family to intimidation and harassment,’” Anderson recalled. He was transferred to Greenville, Mississippi, in the heart of the Delta a region still marked by the visible afterlife of slavery through plantations, sharecropping, and crushing poverty.

“I had experienced some forms of poverty,” he said, “but I had never encountered the kind of Black poverty in the Mississippi Delta. It was horrendous.”

As the 1960s intensified, Anderson saw another threat moving through the movement: the Vietnam War.He believed the U.S. government used the draft as a calculated strategy to weaken Black organizing.

“There was a clear strategy to use the military apparatus to decimate SNCC and other people in the Civil Rights Movement,” he said. “It was not something that I wanted to be complicit in.”

In November 1966, he fled to Canada. In Montreal, Anderson lived under an assumed identity for 11 years, unable to tell his family where he was.

“At intervals, [I would] risk making a call from a pay phone,” he said, “just to let them briefly know that all was well with me.”

Then, in 1977, President Jimmy Carter granted amnesty to draft resisters, making it possible for Anderson to return to the United States. When he finally did, the feeling was complicated.

“It felt like home in many respects,” he said. “But in more respects, it was no longer home.”

The realization hit hardest in conversation with family.

“They would say, ‘What do you think of your president?’ And my response was, ‘He’s not my president. I have a prime minister.’”

He also enrolled at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia), under his assumed name, and found a home in the creative writing program. In 1973, he was awarded the Board of Governors Medal for Creative Expression in Literary Arts.

But his impact wasn’t limited to classrooms. Anderson described decades of community-building work: helping establish Black research initiatives, co-founding cultural organizations, contributing to Black newspapers, and participating in coalitions that pushed Montreal to recognize Black History Month work he believes made Montreal one of the first Canadian cities to do so.

He spoke with visible pride about being selected as one of 12 Black laureates featured in this year’s calendar by the Round Table on Black History Month.

“It’s something I did not expect,” he said, “but something which I’m really proud of.”

The reason the book came into existence was not a publishing strategy. It began as something smaller: a document for family, for children, for memory. But Anderson noticed something happening around him.

“I was hearing from people that so many of the people that I had struggled with were dying” he said. “And those stories remained untold.”

“Three of us were successful in getting our memoirs published,” he said. “Unfortunately, the other four died before they could complete that mission.”

That loss sharpened the stakes.

“It was incredibly important that we got our stories out,” he said, “not just for ourselves but for all the unsung heroes.”

Writing it, he admitted, was not easy. “A lot of the things were very, very painful and disturbing to revisit,” Anderson recalled.

Near the end of the interview, I asked him he defines freedom. His answer came with a warning.

“Freedom is a constant struggle,” he said naming the old freedom song that still rings true. He spoke about rollbacks, political regression, and the danger of forgetting.

And perhaps that is the clearest reason he wrote Eyes Have Seen: because silence is a luxury the movement never had, and memory is too precious to leave behind.

Eyes Have Seen: From Mississippi to Montreal, is published by Baraka books and is available on their website: https://www.barakabooks.com/catalogue/eyes-have-seen/ as well as through major online retailers.