“You done messed up, you forgot something,” that’s what my father said to me in the Covid spring of 2020. He had just tuned in to my CBC Radio-One show “Let’s Go” on a Friday afternoon @ 5pm. I was doing my Friday music segment and the theme was “Classic Instrumental Television Theme Songs That Became Hits.”

“You done messed up, you forgot something,” that’s what my father said to me in the Covid spring of 2020. He had just tuned in to my CBC Radio-One show “Let’s Go” on a Friday afternoon @ 5pm. I was doing my Friday music segment and the theme was “Classic Instrumental Television Theme Songs That Became Hits.”

So while I was waxing poetic talking about theme songs from classic t.v. shows like “S.W.A.T.” and “Hill Street Blues”, my dad shared this with me right after I called him at home to get his approval like I did after every broadcast I did in my 30 plus years in radio and television.

“The Peter Gunn Theme was the biggest instrumental hit. You forgot that one. You got to correct that”.

He was referring of course to the 1959 hit by Henry Mancini that won an Emmy and two Grammy’s from the NBC private detective series starring Craig Stevens. That was my dad. He wasn’t being cankerous. He wasn’t being critical. He wasn’t being unsupportive. He was being dad. The dad that wanted me to be the best from the day I entered this world in the fall of 1969.

I was that special to Pops and he was that special to me.

Wendell Murray Eatmon passed away in my arms at 12:35pm last Sunday on Sept. 5, at The Lakeshore General Hospital. My dad had debilitating stroke just months after the Peter Gunn correction and it seemed to go downhill from there.

Yet my dad stuck around for almost two years. Not because he needed to and maybe even wanted to. He stuck around because he knew me, myself, my brother Jesse-Lee, his 9 grandchildren and my mother Linda, his wife of 53 years were not quite ready to let him go yet.

As a matter of fact, my dad passed away in my arms in the hospital the day before their 53 wedding anniversary.

The reason I held him in my arms while he took his last breath was because I especially couldn’t let him go.

You see, I was my dad and my dad was me. The only thing that differed was that he was great.

My dad was born Oct.28th 1941 in Elm Hill, New Brunswick, one of the 1st Black settlements in Canada. My family like most families in Elm Hill were runaway slaves from Virginia, who were given plots of land to farm on in exchange for allegiance to the British crown, following The Revolutionary War that broke out in the U.S. in 1774 between Britain and The U.S.

My father was born to my grandfather Edwin Eatmon, a WW II vet and my grand-mother Mary Haines, a self-taught musician and singer.

My dad grew up on the Elm Hill farm along with my grandfather Edward Haines and his wife Olive.

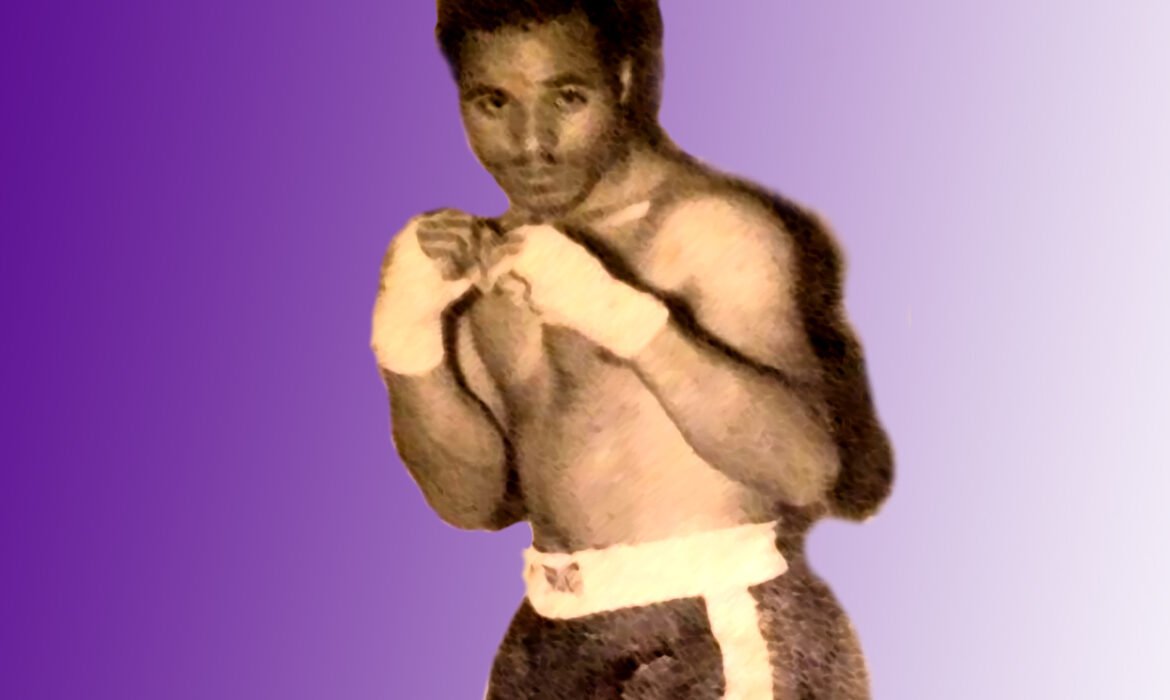

My father started boxing when he was a kid and eventually found his way to Montreal later on when he became one of the top amateur Middleweights and Light-Heavyweights in the province. Many times during Can-Am tournaments in the States, pops was the only one to come back with a medal.

My dad was trained at The Loisirs St. Jean De Baptiste by Louis Hebert, the same man who trained future World Middleweight Champion Otis Grant of Montreal.

But Pops had three things going against him. He was Black. He was a southpaw and he was a devastating puncher.

The powers that be in the Quebec world of boxing therefore meant that my father was not going to be allowed to be a successful professional fighter without having to being involved in unsavory activities like throwing fights, something that my father’s Elm Hill Black upbringing would not allow him to do.

So he met my mother when she was 16. He was 25. They were inseparable ever since. They met in the mid-60’s in a record store that my mother managed on Ontario St.

You see the whole music and me was in the cards from the beginning.

My mother would camp out to get James Brown tickets at the Montreal Forum for the three of us. Center stage, 5th row, where I danced all night in the aisles and sang every word to The Godfather’s hit “Soul Power” like I was a member of his band. I was barely 3 years-old.

My dad put me on stage with Chuck Berry at The Steel Pier Theater in Atlantic City, N.J. when I was a year-old. A few years later, he had me shaking hands with Harold Melvin And The Blue Notes after their concert in the same city. I wasn’t even 6.

He would have me study the lyrics of the great Sylvester Stewart, a.k.a. Sly Stone. He would break out the album “Fresh” by Sly And The Family Stone and play the opening track on side 1, “In Time”. The opening lyrics were; “There’s a mickey in the tastin’ of disaster”. My father would ask me what I thought that meant and of course he would then explain it to me. At 6, I really had no cotton pickin’clue.

He played me the 1950 blues hit “Rollin’Stone” by Muddy Waters and would explain to me that that’s where the funny looking guys from England got the name of their band from.

Of course, everything that pops said to me was the truth and he could do no wrong. He was my Black Superman.

And then I became a teenager.

We clashed as two generations of fathers and sons clashed. For a moment I stopped believing everything he said was the truth. He wasn’t my Black Superman anymore…

But then he said those magic words to me when I was 18.

He found a way to reconnect with me by bridging his generation with mine. He found a way to fill that chasm of difference. He found a way to connect with me again.

He said….“Prince is bad! That boy is bad! He could have hung would any of the greats of my generation. Your boy is great. He’s The Real Deal”!!!…

All of a sudden, he spoke nothing but the truth again. He was my Black Superman once more. Never to be doubted again.

He was my Black Superman by my side through a messy divorce and custody battle.

He was my Black Superman when he taught my son Nathan how to catch a pop fly. Nathan is now in a Nebraska College on a baseball scholarship.

He was my Black Superman when I was laid up in the hospital for ten days when I almost lost my leg.

He was my Black Superman when Prince died in April of 2016 and I cried like a baby.

He was my Black Superman when we would watch Jeopardy during the last years of his life when he would guess most of the answers on the show, whose topics would range from Literature to Norse Mythology.

He was my Black Superman whenever I needed love or someone to talk to.

He was my Black Superman when he taught me all that I know about Black History and Music.

He was my Black Superman every time I won a award because of my broadcasting achievements because I would not have won anything had he not taught me what I know in the 1st place.

He was my Black Superman when took his last breath in my arms on Sept.5th because he was my dad..

“I love you pops! It’ll be a long-time before we see another one like you….”