One of the takeaways filmmaker Michèle Stephenson has from her most recent documentary is that statelessness is an example of extreme anti-Black racism: “it is bureaucratic violence and it’s state sanctioned … we have to eliminate that.”

One of the takeaways filmmaker Michèle Stephenson has from her most recent documentary is that statelessness is an example of extreme anti-Black racism: “it is bureaucratic violence and it’s state sanctioned … we have to eliminate that.”

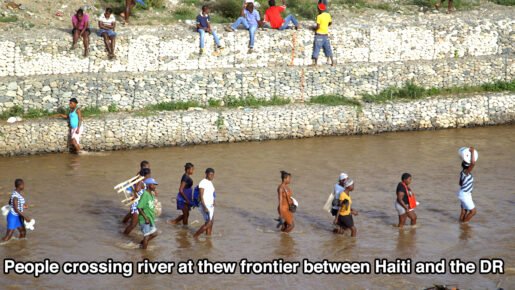

The former Montrealer spent more than five years completing Stateless, a revealing documentary that pried into “the depths of racial hatred and institutionalized oppression” behind the Dominican Republic’s act to denationalize more than 250,000 Haitian born nationals and their children.

On September 23, 2013 the DR’s Constitutional Court ruled retroactively that anyone born after 1929, who does not have at least one parent of Dominican blood cannot claim citizenship to the country.

Stephenson, an award-winning filmmaker born in Haiti, now living in New York says she was so provoked by that ruling, that she felt compelled to take her story-telling skills-set to the island of her birth and peer into the divide that has highlighted much of the history of the

Dominican Republic and Haiti.

She categorizes the story of statelessness in the DR as a racial cast system that

disenfranchises Black

people.

To tell the story, the filmmaker follows a dynamic, young attorney named Rosa Iris Diendomi Álvarez as she mounts a grassroots electoral campaign to win a seat in the congress of the DR and advocate on behalf of her cousin, Juan Teofilo Murat and hundreds of thousands of other persons of Haitians descent rendered stateless by the court decision.

To tell the story, the filmmaker follows a dynamic, young attorney named Rosa Iris Diendomi Álvarez as she mounts a grassroots electoral campaign to win a seat in the congress of the DR and advocate on behalf of her cousin, Juan Teofilo Murat and hundreds of thousands of other persons of Haitians descent rendered stateless by the court decision.

(Rosa Iris’ unrelenting commitment to human rights made her a formidable political force in the DR, but also made her a target and she was forced to seek asylum outside the country.)

Stephenson says while Stateless opens a window on “the dynamics of race in this part of the Caribbean, there’re other parts of (the region) that has similar attitudes.”

More importantly she says: “It can also be a mirror for us and maybe help us see the racial caste system that exist within our communities that we’re a part whether it is in Montreal or here in New York where I live.

How are Black people being disenfranchised in these places, that are similar and where there’s a connection.

The flip side of that is hoping that people are inspired by the work that Rosa Iris is doing, the type of person that she is in and her unrelenting fight for others.

There are thousands of Black women like Rosa Iris who are working in the Haiti, the DR in Montreal and around the world. It is for us to recognize how can we support that work, how can we lift up their work and recognize as well the inequities in our communities.”

She added that the documentary, which highlights universal themes of access to citizenship, migration and systemic racism, should serve as both a window and a mirror.

Pointing to the US, she says: “we are witnessing the chipping away at immigrants’ and citizens’ rights.”

And to the global crisis of “white supremacist manipulation of migrants’ rights, birthright citizenship, and human dignity for Black and brown people.”

Stephenson, who spent her formative years in Montreal attending Vanier College and McGill University eventually earned a Law degree at Columbia University in New York intent on building a career as human rights lawyer.

However, she was drawn to filmmaking as recognized the power of storytelling. She was also influenced by her husband, Joe Brewster an acclaimed filmmaker, with whom she co-founded the Rada Film Group.

Together they brought a lot of creative heft to Stateless.

Their 2012 documentary film American Promise has snagged awards at the Sundance, New York and Hot Springs film festivals.

Stephenson says while she is hopeful that the documentary keeps the spotlight on the issue statelessness, she is not convinced that the UN’s pledge to eradicate the phenomenon by 2024 will happen.

As such, it’s important to keep the issue in the consciousness of people around the world.

And she invites all Montrealers to share in the enlightened experience Stateless offers.

Stateless opens in theatres in Montreal on August 20 at the Cine du Musée and Cinéma du Parc.

Michèle Stephenson’s Stateless unwraps layers of institutionalized oppression